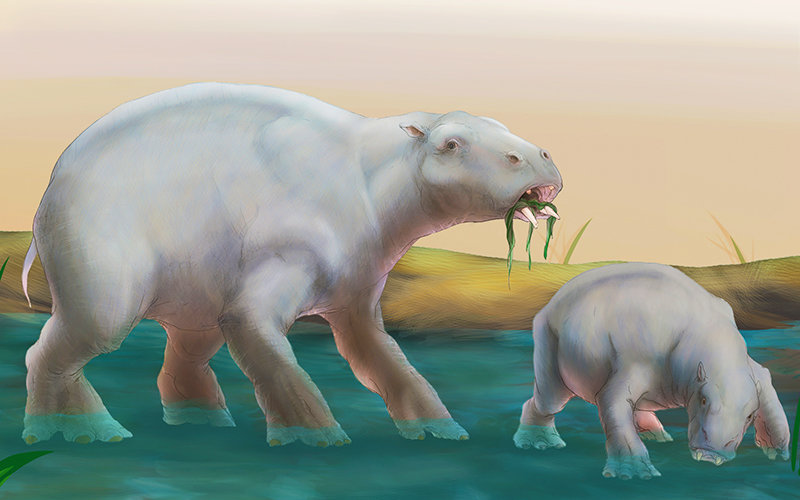

Cal State Fullerton graduate student Gabriel-Philip Santos has uncovered a fossil from Orange County — an 8-to-13 million-year-old member of an extinct group of herbivorous marine mammals called desmostylians, a hippo-like looking animal.

For the past three years, Santos has studied the fossil, a partial jaw of the desmostylian, found in 1996 during construction of the State Route 241 toll road, near Mission Viejo.

Santos’ research focuses on the age and growth of desmostylians, revealing that the John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center fossil specimen is an individual that lived to an old age — the most elderly ever found.

“We don’t know how many birthdays this desmostylian had, but based on its lost teeth, there is evidence that the animal was able to survive into old age,” said James F. Parham, assistant professor of geological sciences and faculty curator of paleontology at the Cooper Center, a partnership between CSUF and OC Parks.

“Since scientists have yet to find a desmostylian that has lived longer, this one provides a unique opportunity to understand how these mammals grew and aged.”

Santos is the lead author of the study published today in the peer-reviewed Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Parham and Brian L. Beatty, associate professor of anatomy at New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine, are co-authors.

“What makes this specimen significant is that there is evidence that the animal was able to survive into old age, even after it lost its teeth,” said Santos. Desmostylians get their name from their unique teeth, Santos explained, which look like a group of pillars, or “desmo,” Greek for bonded, and “stylus,” Greek for pillar.

As a boy who loved dinosaurs and science, Santos decided to become a paleontologist and began volunteering at the Cooper Center in 2011. A year later, he enrolled at CSUF to pursue a master’s degree in geology and is on track to graduate in August. Last September, he landed a position managing the fossil collection at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology in Claremont.

What has it been like to work on this study?

Publishing my first paper as a student has been beyond amazing. Overall, this experience is something that has really prepared me for my future as a paleontologist, and it’s definitely something I won’t ever forget. The best thing about this experience has been the collaboration and mentorship with Dr. Parham and Dr. Beatty. Dr. Parham, who also is my graduate adviser, taught me so much about how to be a great scientist and how to ask the right questions.

What excites you about this work?

The significance of this study is that we now have a more complete idea of what happens to desmostylians, specifically the genus ‘Desmostylus,’ as they get older. This study could help future studies in identifying other specimens that were fossilized at different stages in their lives, as well as help us learn more about desmostylians as a species. There is so much we don’t know about these animals, and every discovery brings us closer to understanding what these really unique animals were like. These animals are such mysteries, and getting to unravel those mysteries really appeals to my love of paleontology and satiates my thirst for knowledge.

How is this experience helping you reach your academic and career goals?

I feel like this publication is my first foray into the science of paleontology. I’ve learned the essentials of what research, and what being a scientist, truly are. Using those essentials and gaining a better understanding of what my purpose as a scientist is, I can now go further and do bigger, better research projects that seemed impossible to me when I first started thinking about being a paleontologist.