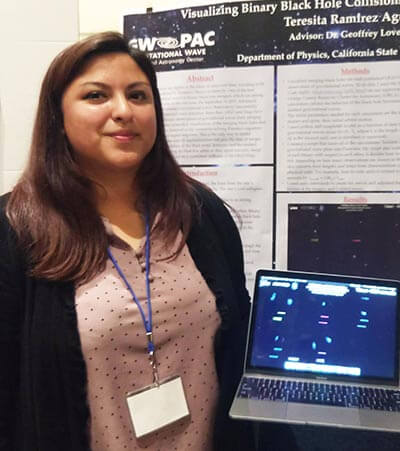

Cal State Fullerton undergraduate physics researcher Teresita Ramirez Aguilar is learning to use supercomputers to create and visualize simulations of colliding black holes that produce gravitational waves — and is making waves of her own. Her research appears in today’s (Dec. 3) announcement by LIGO and Virgo of four new gravitational-wave detections from black-hole mergers.

The National Science Foundation-supported LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) and the European-based Virgo gravitational-wave detector have now confidently detected gravitational waves from a total of 10 stellar-mass binary black hole mergers and one merger of neutron stars, which are the dense, spherical remains of stellar explosions, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration announced. Six of the black hole merger events had been reported before, while four, all discovered in 2017, are newly announced.

All of the gravitational-wave events are included in a new catalog, released Dec. 1, with some of the events breaking records. The new event called GW170729 was detected in the second observing run on July 29, 2017, and is the most massive and distant gravitational-wave source ever observed. In this coalescence, which happened roughly 5 billion years ago, an equivalent energy of almost five solar masses was converted into gravitational radiation.

The simulation that Ramirez Aguilar, a junior, created for the announcement, with research adviser Geoffrey Lovelace, associate professor of physics, uses computer calculations to model the gravitational waves LIGO has observed to date, as well as the black holes that emitted the waves. The image shows the horizons, or surfaces, of the black holes above the corresponding gravitational wave.

Lovelace and physics colleagues Joshua Smith and Jocelyn Read — all members of the international LIGO Scientific Collaboration — and their student researchers at CSUF’s Gravitational Physics and Astronomy Center (GWPAC) have played significant roles in the detection of gravitational waves since the first gravitational wave discovery was announced by LIGO in 2016.

Beginning in 2015, second-generation LIGO detectors observed gravitational waves for the first time, giving scientists a new sense to observe the universe. The physicists and their students played key roles in discoveries of gravitational waves in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Read, an astrophysicist and associate professor of physics, and her students were part of the first discovery of gravitational waves from neutron stars in 2017.

Smith, professor of physics and Dan Black Director of Gravitational Wave Physics and Astronomy, postdoctoral research associate Marissa Walker, and student researchers are continuing to work on understanding and minimizing the noise in LIGO detectors, which helps to recover the waves from the detector data.

While Read and her students played leading roles in LIGO’s first observation of merging neutron stars, which is the loudest wave in the catalog, their work continues to focus on learning about how neutron star matter behaves.

The ongoing work of Lovelace and his students, including Ramirez Aguilar, focuses on using supercomputer calculations to model the merging black holes that LIGO and Virgo detect.

“These models help us interpret what kinds of black holes emitted the waves LIGO and Virgo observed,” Lovelace said.

For the past two years, Ramirez Aguilar has been involved in immersive research with Lovelace, where she is learning how to use computer code to solve the equations of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, called the Spectral Einstein Code. She performs the numerical relativity simulations of colliding binary black holes on the GWPAC’s National Science Foundation-funded supercomputer.

“This research is so cool because I get to learn about some of the craziest phenomena in our universe,” said Ramirez Aguilar, a research scholar in the Louis Stokes Alliances for Minority Participation program at CSUF who plans to pursue a doctorate in physics.

“It’s important that we get people interested in science, and creating visualizations like these are important for public outreach. They not only help to ignite interest in gravitational-wave science, but also help give intuition into the kinds of black holes observed, such as their different shapes and sizes.”

Since the second observing run ended in August 2017, LIGO — with detectors in Washington and Louisiana — and Virgo have undergone major upgrades to make detectors more sensitive. The next observing run is scheduled to start in spring, and is expected to yield even more cosmic objects and gravitational waves, Lovelace said. For more about the latest National Science Foundation support for CSUF gravitational-wave science, continue reading here.