Aerosol particles are microscopic liquid or solid particles suspended in the atmosphere. These particles are too small to see, but become visible on a hazy or smoggy day, when objects in the distance look indistinct and have a brownish-yellow color.

These particles have many different sources, such as smoke from wildfires or soot from cars and trucks. Some particles, such as smog — an aerosol composed of particles — form in the atmosphere through a series of chemical reactions from air pollution.

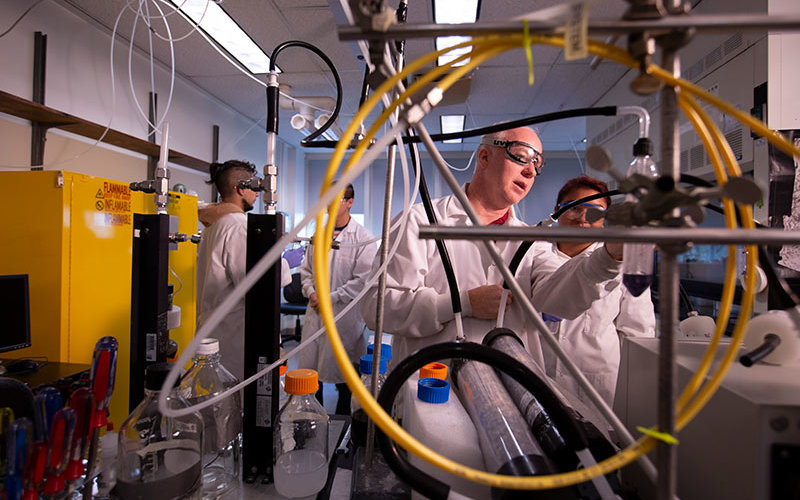

Researchers Paula K. Hudson and Daniel B. Curtis, both associate professors of chemistry and biochemistry, and their students are working on a joint project to determine how aerosol particles affect climate change.

“We don’t know if aerosol particles from human activity have a net warming or cooling effect on Earth’s climate,” Curtis says.

“Our research will benefit society by helping to figure out how particles in the atmosphere may contribute to climate change. Historically, aerosol particles were thought to counteract greenhouse gases and cool the Earth down. But scientists now know that some types of aerosol particles can actually make climate change even worse.”

Curtis and his students are focusing on whether the scattering and absorbing properties of aerosol particles will warm or cool the Earth — and by how much.

“If the particles only scatter light, they reduce the amount of sunlight reaching Earth’s surface and can cause the Earth’s temperature to cool,” he shares. “But if the particles absorb sunlight, they can act to warm up the Earth. This is similar to if you wear a white shirt on a sunny day, the light is reflected and it keeps you cooler. If you wear a black shirt on a sunny day, the light is absorbed and you feel warm.”

Hudson and her students are studying the chemical reactions that form “brown carbon,” which is found in smoke particles from wildfires and smog particles from urban pollution. Brown carbon might warm the Earth because the particles absorb light in the atmosphere, which in turn may cause even more fires in such places as California, she shares.

The research team is designing lab experiments to try to figure out if the brown carbon reacts with other compounds in the atmosphere that do not absorb light. To carry out this research, both labs use various sophisticated and high-tech instruments, funded by a $368,000 National Science Foundation grant and a 2018-19 CSUF Research, Scholarship and Creative Activity Incentive grant, to measure the chemical properties and reactions of aerosol.

“We would like to know what happens to the brown carbon once it is in the atmosphere. How does it go away? We have measured that brown carbon absorbs blue light more strongly than red light, which gives it its distinct brownish-yellow color,” Hudson says. “We also have measured that the formation of brown carbon in the atmosphere occurs faster at higher temperatures.

“So far, we have determined that brown carbon absorbs visible light and can contribute to climate change.”