As an undergraduate, geology alumna Sierra Patterson embarked on a study to help resolve an archaeological problem with geologic tools.

Patterson, alumnus Ryan McKay and their faculty research adviser Valbone “Vali” Memeti focused on learning more about the mystery of cogged stones. These ancient Native American artifacts are found in Southern California, including Orange County. The cogged stones were carved from various rock types into the shape of a hand-sized cogged wheel.

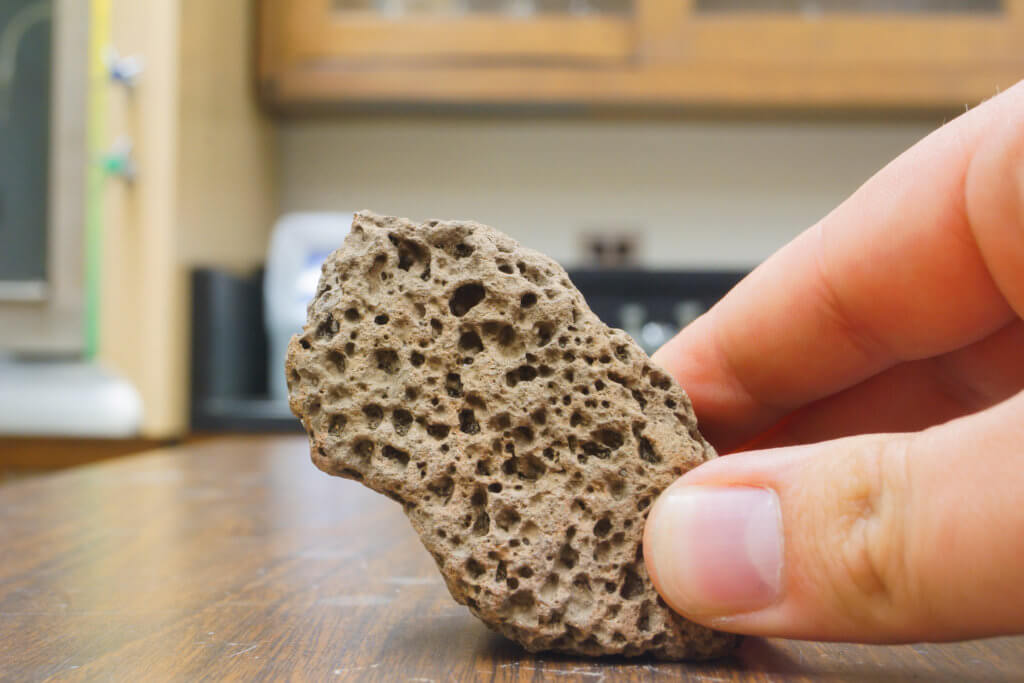

One of the most commonly used rock types to carve the cogged stones is the basaltic scoria, a type of volcanic rock, said Memeti, assistant professor of geological sciences.

The function of the cogged stones — found at 8,000- to 3,500-year-old sites in Southern California — are the subject of debate by archeologists. The researchers’ goal was to help reveal the enigma around the cogged stones and determine the source of the basaltic rock used to carve them, Memeti added.

“The thought was that maybe if we knew where the scoria came from by fingerprinting the origin of a few fragments of cogged stones and the rocks exposed in Southern California using the mineral content and geochemical characteristics, we could help narrow down the meaning or uses of the artifacts by the Tongva tribe,” Memeti said.

Their research was recently published in the peer-reviewed journal California Archeology, concluding that the rocks from which the cogged stones were carved were derived from nearby rock sources unique to Orange County.

While how cogged stones were used by early Native Americans is unknown, in their paper, the CSUF researchers noted that since the stones were first discovered in the 1950s, more than 40 possible uses have been suggested for these artifacts by archaeologists. Hypothesized uses in previous studies include use as fishing weights, for the manufacture of fishing lines or rope, toys, game pieces, throwing weapons or killing stones. Alternative hypotheses proposed include their use as sacred burial, mortuary and ceremonial objects.

The research project was the basis of Patterson’s and McKay’s undergraduate thesis. Patterson, a park ranger at Yosemite National Park, is first author on the publication, with McKay, who works at an environmental consulting company, and Memeti co-authors. The researchers examined the collection of cogged stones at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, as well as samples from other local museum collections, and collaborated with several other scientists.

“I hope that our work gives other researchers a starting point and sheds some light on the possible use of cogged stones,” Patterson said.

Analyzing Cogged Stone Samples in Search of Answers

For the research, four cogged stone fragments were donated from the Orange County Archaeological and Paleontological Center in Santa Ana for analysis, with the focus to determine the origin of the rock, Patterson said. Memeti received a CSUF Faculty Mentorship of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities grant to fund the project.

The researchers used geological techniques to look at the compositions of the cogged stone fragments from excavations between Costa Mesa and Laguna Niguel, including the Bolsa Chica Mesa area. They also examined 40 potential source rock samples of basaltic scoria from locations across Southern California to compare to the cogged stone fragments.

Out of the four cogged stone fragments that were analyzed, it was determined that there were two matches and one possible match. The two matches came from the El Modena Open Space area in Orange and the Santa Rosa Plateau, the southern extension of the Santa Ana Mountains, west of the city of Murrieta. The possible match came from Catalina Island.

“This research is important because the two matches indicate that the cogged stone material was locally sourced and helps other scientists narrow down the possible uses for the cogged stones,” Patterson said. “It should be of interest to people because it helps place a missing piece of the puzzle for a historical object.”

Patterson and Memeti worked for three years to turn the undergraduate research into a published scientific paper.

“After a few years of edits and countless versions, we finally had a paper worthy of journal submission,” Patterson said.

At CSUF, Patterson also had the opportunity to travel to Chiang Mai University and study the geology of northeastern Thailand with Brady P. Rhodes, professor emeritus of geological sciences. The program gave her insights on how research and collaboration is achieved globally throughout the scientific community.

Patterson and McKay, who both earned a bachelor’s degree in geology in 2016, presented their research at conferences. Participating in undergraduate research gave them laboratory and fieldwork skills to prepare them for the workforce.

“My research allowed me to achieve something on my own that showed me the hard work, determination and dedication a career in geology would need,” shared Patterson, who after graduation worked on earthquake and natural disaster research for the U.S. Geological Survey.

“Dr. Memeti also could not have been more supportive. She was always available to answer questions and was there for anything that I needed. Without her support and guidance, this research project would not have been as successful.”