With outbreaks of infectious diseases on the rise — most recently the Zika virus — Cal State Fullerton scientists and their students are conducting studies to help understand and stop the spread of infections.

For the past decade, Paul Stapp, professor of biological science, and his colleagues have been studying the ecology of plague in Colorado’s black-tailed prairie dogs.

The National Science Foundation-funded, multi-institutional research offers significant insights into the study and tracking of zoonoses, infectious diseases that are transmitted by animals to humans, said Stapp. The study demonstrates how plague spreads across the shortgrass prairie landscape, wiping out entire colonies of prairie dogs.

The lessons learned from such research can help in the study of other zoonotic diseases, including the Zika and Ebola viruses. Zika, transmitted by mosquitoes, has spread from Africa to across the Americas. The disease may have serious consequences for pregnant women, with some babies born with severe birth defects. This week, the World Health Organization declared Zika a global public health emergency.

“To truly understand the risk to humans, we need to know about the ecology of disease in the wild populations that are involved in spread,” Stapp said.

The collaborative research represents one of the most comprehensive studies of the ecology of any disease system, revealing aspects of the biology of multiple vector and host species and their interactions, Stapp explained.

Plague is a bacterial disease spread by rodents and their fleas that is best known for killing millions of people during past epidemics. Epidemics still occur in developing countries, Stapp noted. The pathogen was introduced to the United States at the turn of the 20th century, with the last urban epidemic in 1924 in Los Angeles.

Stapp added that the study shows that plague outbreaks are likely influenced by climate patterns, such as El Niño. Some experts suggest that El Niño, which could significantly increase populations of exotic mosquito populations, has contributed to the spread of the Zika virus.

Stapp and his colleagues’ research was published last month in BioScience, a journal of the American Institute of Biological Sciences. Lead author Daniel J. Salkeld of Colorado State University was a postdoctoral scientist in Stapp’s lab in 2005-06. Stapp’s students made significant research contributions, resulting in thesis projects of four graduate students and projects of two undergraduates. Their lab and fieldwork also resulted in 18 peer-reviewed scientific articles and more than 15 conference presentations and seminars.

‘Kissing Bug’ Disease

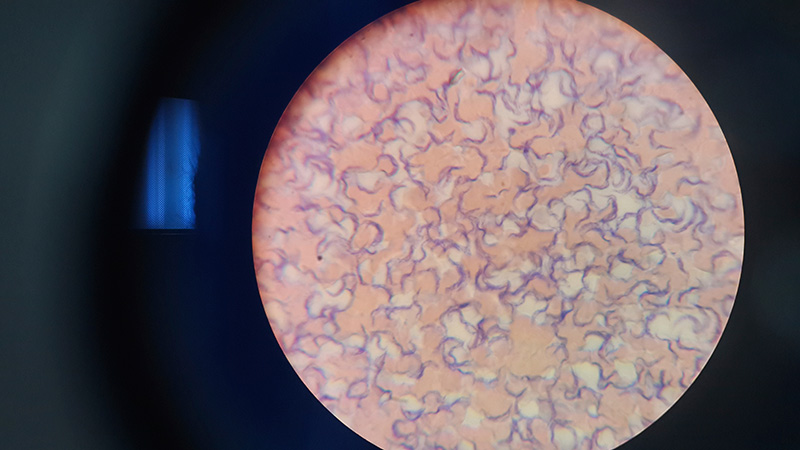

Veronica Jimenez, assistant professor of biological science, and her students are studying a parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes Chagas disease and is transmitted to animals and people by an insect vector similar to what happens with the Zika virus.

In Chagas disease, the insect vectors are blood-sucking triatomine bugs. Infected by the parasite, the bugs, in turn, infect humans by biting a person’s face, earning the nickname “kissing bugs.”

Chagas disease affects millions of people in Latin America and Africa, and last year, an increased number of cases was reported in Texas. Due to such increases in the U.S. and Europe, it is considered a global emerging disease, Jimenez said.

The parasite multiplies and travels through the bloodstream to tissues and even the heart, possibly leading to life-threatening cardiac complications and other health problems, Jimenez said. Pregnant women also can transmit the infection to their babies in the same way as the Zika virus.

“There is no cure and no vaccine for Chagas disease,” said Jimenez, who grew up in Argentina and worked in public hospitals, where she saw newborns and adults infected.

Jimenez and her students are investigating how the parasite is able to adapt, survive and multiply in changing and different environments, as well as infect different organisms — from people to cows, dogs, cats and other mammals.

“The problem is we know so little about these parasites. We need more research to fight these bugs, including developing new drugs and treatment options that impair the parasite’s ability to survive,” Jimenez said.