While working as a high school athletic trainer and biology teacher in 2010, Tricia Kasamatsu noticed a lack of academic support services for athletes returning to class after a concussion.

In particular, a football player recovering from an accidental blow to the head worried about falling behind in his coursework. Committed to graduating on time, he approached Kasamatsu for assistance.

The experience inspired her to begin researching ways to support student-athletes in similar situations, ultimately pursuing a doctorate in education and joining Cal State Fullerton as an assistant professor of kinesiology to teach best practices to future athletic trainers.

What are your research areas?

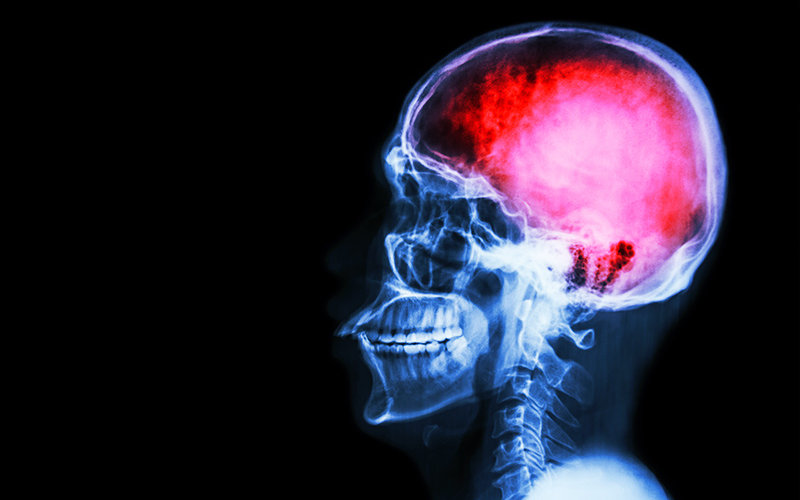

As health care professionals who are often employed in schools, athletic trainers play a key role in the management of concussion. Most of the research that I do is trying to understand what high schools are doing to help prevent, assess and then manage concussions. I’m also very interested in the support that’s available for students when they return to school.

We’ve focused a lot on “return-to-play,” but until recently we’ve neglected whether or not their brains are prepared to “return-to-learn.” Generally, we’ve seen that teachers, school counselors and administrators have a positive perspective toward supporting students after a concussion, but aren’t quite sure of the specific academic adjustments they can provide.

What are some examples of academic adjustments after a concussion?

Academic adjustments can include, but are not limited to, delaying due dates on assignments, giving extra time for test-taking, allowing students to wear sunglasses if they experience sensitivity to light, or modifying visual resources so they don’t have to look up and down from the board to their notes. Strategies like these are meant to be targeted to each student’s needs, rather than used as a blanket policy. If a concussion takes longer than one or two weeks to heal, there are more formal procedures for obtaining long-term help.

What progress has been made to ensure the head safety of athletes?

In the past few years, a lot of states have picked up concussion legislation with “return-to-play” policies — that is, a person suspected of having a concussion in high school, college or professional sports cannot return to play until he or she is cleared by a medical professional — and even some “return-to-learn” policies. We also have new legislation in California about youth sports, Assembly Bill No. 2007, which applies the same “return-to-play” guidelines. This legislation may be even more important because young children often don’t have access to athletic trainers or campus resources.

We have much better knowledge about proper helmet fitting and active treatment options, and many sport rulings have changed. For example, organizations like the NFL and NCAA have moved the kickoff line so athletes have less time to build momentum and have enacted penalties for directly targeting a hit to the head. As we continue to learn more, we can create environments that are safer for athletes.

What can be learned from the recent media coverage of the link between football and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)?

Much of the media frenzy over CTE has led people to speculate and jump ahead of what we know, telling children things like they should retire and not do sports if they’ve had a third concussion before they get out of high school. There still is much we don’t know about CTE and how it relates to concussions because it can’t be studied until a person passes away. For me, the real challenge is: How do you give people enough information so they know CTE is a possibility without scaring them away from all the good things that come from sports participation?