Will the Carl’s Jr. on campus one day be serving jellyfish?

Students in Nicole Seymour’s “Literature and the Environment” class are asked to consider this question after reading Karl Taro Greenfeld’s novel “The Subprimes,” which focuses on the impact of climate change on foodways.

“Jellyfish thrive in rising ocean temperatures, and the belief is that we will probably be eating a lot more of them in the future,” explained the Cal State Fullerton associate professor of English, comparative literature and linguistics. “With this idea in mind, I sent students to Carl’s Jr. and asked them to imagine how the menu might look different in 50 years.”

Seymour, author of “Bad Environmentalism,” is currently working with faculty members from the University of California and California State University systems to develop tools for teaching climate justice and other issues.

From syllabi to assignments, the educational resources will be housed in UC-CSU NXTerra, an open-access repository that launched Nov. 18 and will be globally presented at the 2019 UN Climate Change Conference (COP 25) in Madrid. Seymour’s focus is on curating materials on “climate change and emotions” and “climate fiction.”

In teaching climate fiction, Seymour said she always begins by having students examine the benefits and drawbacks of the term “cli-fi,” coined by journalist Dan Bloom in 2008 to describe the emerging literary genre.

“At a time when some political pundits are still referring to climate change as a hoax, do we really want to associate the concept of fiction with it?”

Regardless of its name, climate fiction can help people understand the factors that have given rise to climate change and worsened its effects, explained Seymour.

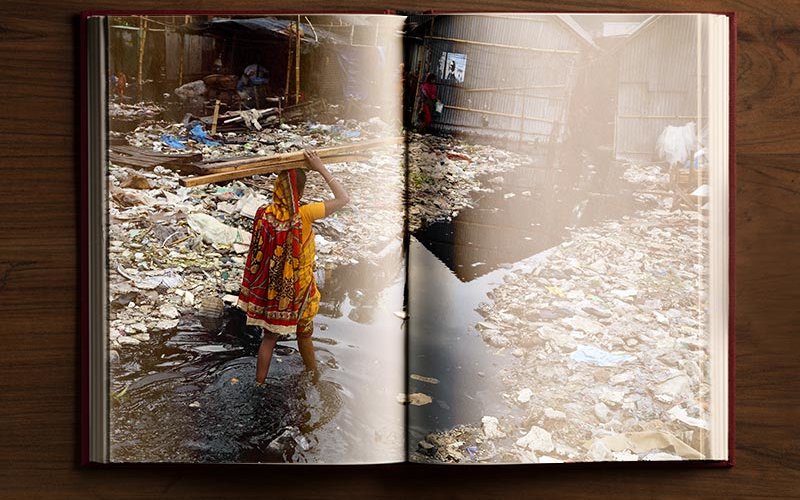

“Instead of potentially overwhelming scientific statistics, ‘cli-fi’ presents human stories that are relatable and engaging,” she said. “‘Cli-fi’ also can highlight the ways in which climate change intersects with social injustices and help us imagine new ways to adapt and live.”

Seymour said novels like Greenfield’s “The Subprimes,” Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” and Nathaniel Rich’s “Odds Against Tomorrow” challenge students to imagine new societies forming in the wake of climate change, widespread income inequality and other interrelated problems.

“Some scholars argue that any fiction produced during this era could count as climate fiction, regardless of how explicitly it discusses the climate crisis,” she said. “In 100 years, people might start looking back at everything we read and wrote during this era for traces of consciousness or politicization around climate change.”