Student Stephanie Hernandez considers herself a steward of Earth. To do her part, she is studying California’s past climates to better understand current and future environmental concerns, including the fight against global climate change.

To find out more about how major floods, fires and droughts played a role in past climates, Hernandez, an earth science major, and fellow Cal State Fullerton faculty and student researchers are working on a first-ever study focusing on California’s precipitation history and comparing it to the past 10,000 years.

The multiyear study, which began in 2017, details the changes of the state’s precipitation — rain and snow — and the causes for these changes, says Matthew E. Kirby, professor of geological sciences, who is directing the research project.

“Our objective is to reconstruct the past 10,000 years of California’s drought — the drier than average periods; the pluvial periods — the wetter than average times; and wildfires in California,” Kirby adds.

“Our research will provide a baseline understanding of natural climate change in California and the reasons for those changes. This information informs policy makers and water managers about the range of expectations and possibilities in our climate system.”

The researchers’ goal is to provide a record of climate change before significant human disturbance, which can be used to compare and contrast recent changes caused by human activities, such as pollution, the burning of fossil fuels and fire behavior.

Preliminary research results indicate large changes in California precipitation over the past 10,000 years, with strong evidence for a major dry period lasting 1,000 years or longer that has not been observed in tree ring records, Kirby notes.

The ongoing research is funded by a nearly $346,000 National Science Foundation grant, with Joe Carlin, assistant professor of geological sciences; Kevin Nichols, associate professor of mathematics; and former mathematics faculty member Reza Ramezan, now at the University of Waterloo in Canada, also collaborating on the project. The CSUF researchers are partnering with UCLA professor Glen MacDonald, John Muir Memorial Chair of Geography, and his students. Nichols and Ramezan will be creating statistical models to compare paleoclimate data from the different lakes.

Looking to the Past to Find Future Solutions

Over the past three summers, the researchers have collected about 262 feet of mud — sediment samples — from six natural lakes along California’s coastal region, north of San Francisco and south of the Oregon border. One of the research trips involved a hired mule team to carry 500 pounds of equipment into the back country to North Yolla Bolly Lake, southwest of Redding. This past summer, the team traveled to Kelly Lake and Big Lake, in the northwest part of the state. Other research sites are Barley Lake, Maddox Lake and Tule Lake. Ultimately, these new lake records will be compared to existing lake records in Southern California already studied by Kirby and his colleagues.

“Like pages in a history book, these columns of mud tell us a history of droughts, pluvials and fires. We then analyze materials in the lab, such as sand, charcoal and pollen in the mud, which tell a story. Understanding how and why climate and fires changed in the past is important to making informed decisions about future climate and fire change in the state,” Kirby points out.

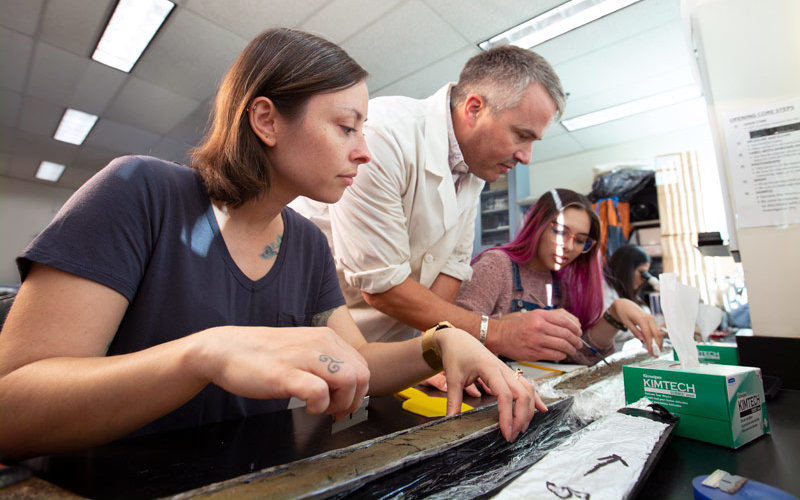

Kirby and his student researchers are continuing to analyze lake sediment samples — the physical, chemical and biological properties — in his campus lab, and are working toward publishing their findings in scientific journals. The first publication is expected in winter, followed by other journal papers over the next several years.

For her senior thesis project, Hernandez is currently focusing on piecing together the climate history of Tule Lake, near Ukiah, and how it fits into the state’s bigger precipitation picture.

“It is a really cool feeling when I find a specimen within a lake sediment sample for radiocarbon dating. I often think to myself, ‘Wow, this seed or pine needle is thousands of years old!’ It truly amazes me,” says Hernandez, who is Kirby’s lead laboratory technician.

Hernandez, the first in her family to attend college, plans on earning a master’s degree and pursue a career as an environmentalist. She hopes her undergraduate research will help to protect future generations from the consequences of climate change.

“It’s important to know and understand the Earth’s history to help us make important decisions about our environment, which in turn will help the people I care about on this planet.”