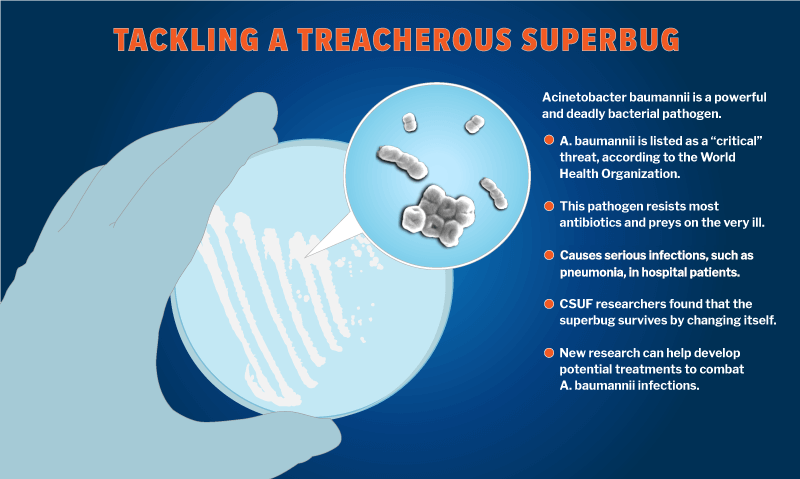

A team of Cal State Fullerton antibiotic-resistance researchers are one step closer to shedding light on why Acinetobacter baumannii, one of the most powerful and deadly bacterial pathogens, is so hard to eradicate in people with weakened immune systems and in hospital settings.

Their latest study, published in July in Frontiers in Microbiology (Infectious Diseases section), calls attention to how this superbug is able to grow and live by adapting to its environment inside the human body.

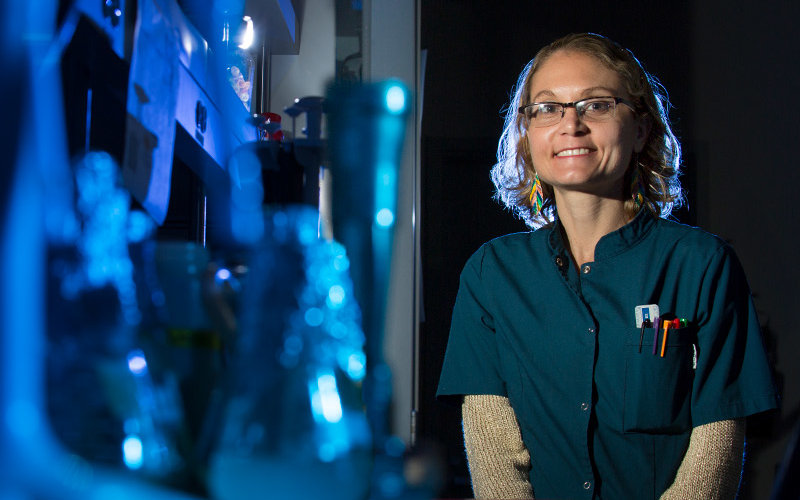

“Our results show how this pathogen can overcome harsh environments within the host by switching its metabolism to survive and persist,” said María Soledad Ramírez, assistant professor of biological science, who led the research team and is a co-author of the paper.

The World Health Organization has assigned A. baumannii a threat level of “critical” on its priority pathogens list. It resists most antibiotics and preys on the very ill, typically causing serious infections in patients in healthcare settings, including hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The study’s findings will help researchers develop new potential treatments or strategies to combat A. baumannii’s infections, said Class of 2018 graduate Nyah Rodman, a medical student studying infectious diseases and public health at UC San Diego School of Medicine, who is the first author of the paper.

“With A. baumannii recognized as among the most treacherous pathogens, our study gives background on how this bacterium works in the context of pneumonia, which can help find options for novel treatments,” Rodman said. “But first, we need to understand how this pathogen is able to protect itself and spread.”

In this study, the researchers exposed A. baumannii to pleural fluid, which is found in the respiratory system. Their work focused on uncovering how this pathogen responds to the pleural fluid, then finding a way to weaken the bacterium’s survival. The team observed that A. baumannii undergoes changes in response to human pleural fluid, and actually increases its toxic effect on cells and its ability to evade the immune system, Ramírez pointed out.

“What was most interesting is the fact that pleural fluid is known to be a detrimental environment for bacteria to grow. However, with A. baumannii, this bacterium finds a different way to survive within this fluid,” noted Jasmine Martinez, a scholar in the university’s McNair Program, which prepares students for doctoral studies, and a co-author of the journal paper.

“It’s amazing that while our body contains different components to help kill bacteria, this superbug finds a way to change itself to become more persistent and thrive within this environment.”

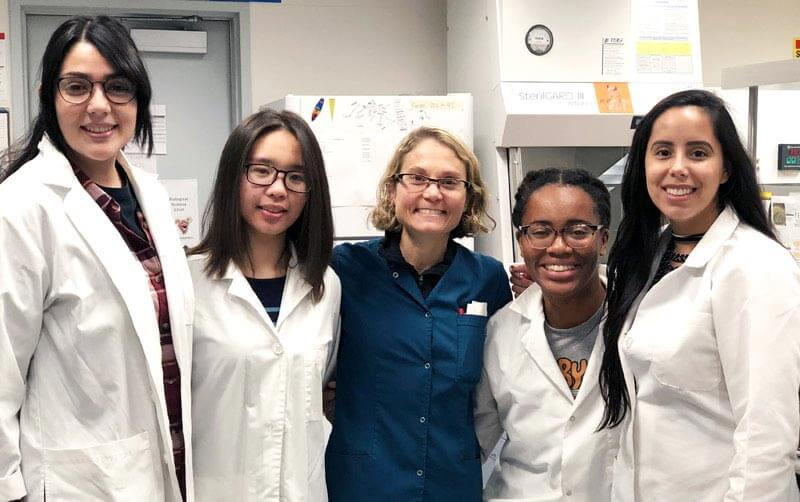

A total of 10 student researchers are authors of the paper, along with three other CSUF biological science faculty members: Catherine A. Brennan, Veronica Jimenez and Nikolas Nikolaidis. Two research collaborators also contributed: Robert A. Bonomo of Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Rodrigo Sieira of Fundación Instituto Leloir in Argentina.

The other student co-authors are undergraduate Christine Liu and graduate student Jennifer S. Fernandez of Ramírez’s lab; and, graduate students Amber L. Myers and Caitlin M. Harris of Brennan’s lab. Jun Nakanouchi, Emily Dang and Anthony M. Mendoza, all Class of 2019 graduates, and Sammie Fung, a former postbaccalaureate scholar, also co-authored the research paper.