Will 2020 be the year for a long-overdue national conversation about stuttering?

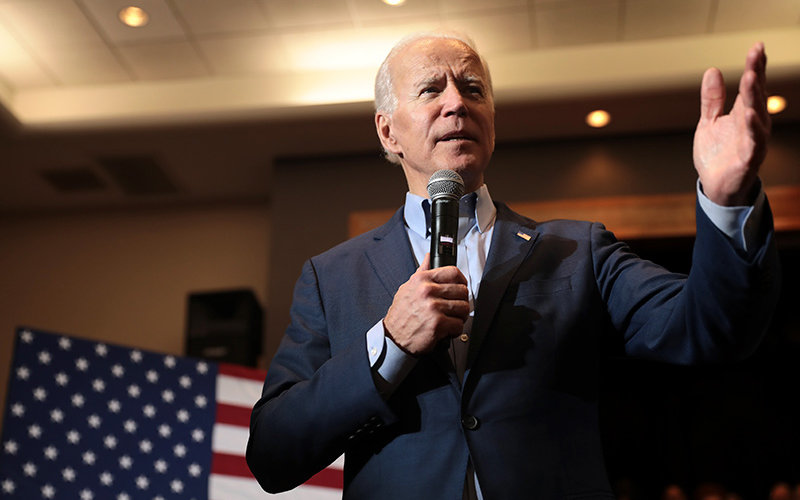

In January, Captain “Sully” Sullenberger wrote an op-ed in The New York Times calling out people who ridicule people who stutter. In February, former Vice President Joe Biden spoke about his lifelong stutter during a CNN town hall event. In this month’s edition of Marie Claire, actress Emily Blunt discusses how her stutter led her to a career in acting.

The Stigma of Stuttering

“Stuttering affects about 1% of the world’s population, across all cultures,” says Ying-Chiao Tsao, associate professor of communication sciences and disorders at Cal State Fullerton, “but it has long been misunderstood and stigmatized. In the old times, it was thought to be an evil spirit.”

People also are confused by the situational nature of the disorder. For example, individuals who stutter can have an easier time when they “put on a different persona” — acting on stage, singing or talking to a pet.

Additionally, misunderstanding and negative stuttering stereotypes have been perpetuated in media, says Robin Ottesen, director of CSUF’s Center for Children Who Stutter. “The general public has associated it with incompetent movie and cartoon characters, lack of intelligence or dishonesty.”

Ottesen is well aware of the stigma, as she herself is a person who stutters.

“The stigma starts pretty early,” she admits. “Children can get bullied, and parents hope therapy will ‘fix’ them. With the best of intentions, lots of pressure is placed on children who stutter.

“As we grow up, we have emotional memories associated with unsuccessful communication, which shapes choices we make,” Ottesen continues. “We gravitate toward jobs where we don’t have to talk a lot.”

Fortunately, she says, self-help organizations backed by celebrities have brought more general public awareness and understanding about stuttering in the last five to 10 years.

Understanding Stuttering

More boys stutter than girls — almost at a five-to-one ratio — says Ottensen. While it’s quite common for preschoolers to stutter, the vast majority spontaneously recover. Only about 1% will have persistent stuttering beyond age 8.

Tsao explains that the understanding and treatment of stuttering began to change in the mid-1990s with brain imaging studies, which suggested a relationship with sensory and motor differences. Such findings were a relief to the stuttering population, providing evidence that their speech disorder was not their fault.

Researchers are also exploring genetic links. “Studies also have shown that stuttering could be 50% genetic,” she adds.

Treating Stuttering

On the treatment side, Tsao notes that “we’ve been talking less and less about techniques or speech drills to address stuttering.” Instead, the focus has broadened to include cognitive behavior therapy and self-acceptance. “Treatment means dealing with the whole person.”

She explains that the goal now is to be a clear communicator. “They can stutter and still be an effective communicator. Joe Biden is a good example of this.

“There is no cure or magic wand,” Tsao continues. “Patients work to accept their stuttering, which is complicated by behaviors like fear and anxiety they have learned in response to stuttering. Cognitive behavioral therapy is used to change those responses.”

Experts on Stuttering

Cal State Fullerton has a rich history of expertise in the area of stuttering. The late Glyndon D. Riley, professor emeritus of speech communication, and his wife, Jeanna Riley, were renowned researchers and leaders in the field.

“There is not a speech-language pathologist who does not know the Rileys’ work,” says Ottesen. “They created the first standardized instrument to assess and measure stuttering, the Stuttering Severity Instrument.”

CSUF’s Center for Children Who Stutter is the realization of the Rileys’ dream to have an entity committed to diagnosing and treating stuttering, especially for those unable to afford private practice specialists who treat stuttering.

The center also hosts an annual conference to share the latest research and knowledge on stuttering with students, faculty, staff and speech-language pathologists from around the world.

Ottesen believes education is key to destigmatizing stuttering and to give hope to those who live with stuttering. Candid talk from people in the public eye — like Biden and Blunt — can go a long way.

“People need to understand how debilitating stuttering can be if you don’t have a support system in place that can really understand what you feel,” Ottesen maintains. “Even if you have what looks like a mild stutter, there’s so much going on inside to be that fluent. Like with any marginalized population, education is the only way to destigmatize it, and that has to come from really brave people who stutter to talk about it more.”

Learn more about CSUF’s Center for Children Who Stutter and the university’s Communication Sciences and Disorders Department.