Cal State Fullerton paleontologists have identified three new walrus species — estimated to be 5 to 10 million years old — discovered in Orange County. One of the new species has “semi-tusks,” or longer teeth.

The other two new species don’t have tusks, and all three predate the evolution of the long iconic ivory tusks of the modern-day walrus, which lives in the frigid Arctic. Millions of years ago, in the warm Pacific Ocean off the coast of Southern California, walrus species without tusks lived abundantly.

“Orange County is the most important area for fossil walruses in the world,” said geology graduate Jacob Biewer, who conducted the study for his master’s thesis. “This research shows how the walruses evolved with tusks.”

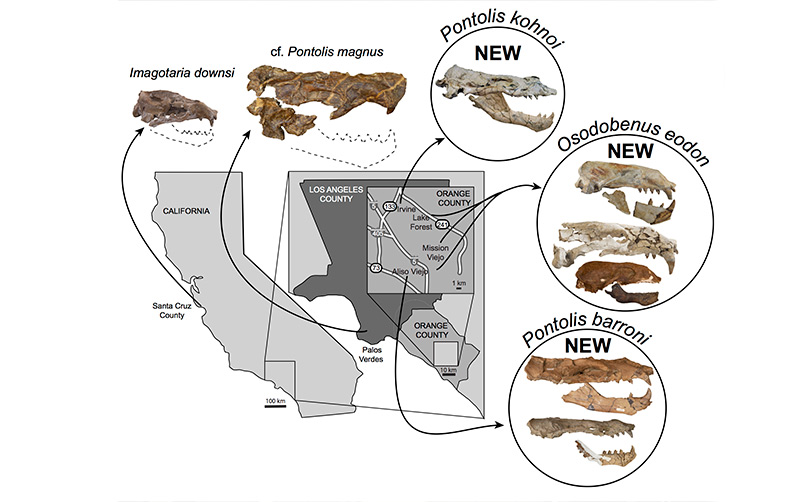

The researchers describe a total of 12 specimens of fossil walruses representing five species from Orange, Los Angeles and Santa Cruz counties. Two of the three new species are represented by specimens of males, females and juveniles.

Their research, which gives insights on the dental and tusk evolution of the marine mammal, was published today (Nov. 16) in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Biewer is first author of the paper, with his research adviser James F. Parham, associate professor of geological sciences, a co-author of the study, based on fossil skull specimens.

Parham and Biewer worked with Jorge Velez-Juarbe, an expert in marine mammals at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and a co-author of the paper. Velez-Juarbe is a former postdoctoral scholar in Parham’s lab and has collaborated on other CSUF fossil research projects. Parham is a research associate at the museum, which provides research opportunities for him and his students.

The researchers teamed to study and describe the anatomy of the specimens, most of which are part of the museum’s collection.

Extinct Walrus Species Get Names

Today, there is only one tusked walrus species and its scientific name is Odobenus.

For the new species found in Orange County, the researchers named the semi-tusked walrus, Osodobenus eodon, by combining the words Oso and Odobenus. Another is named Pontolis kohnoi in honor of Naoki Kohno, a fossil walrus researcher from Japan. Both of these fossils were discovered in the Irvine, Lake Forest and Mission Viejo areas.

Osodobenus eodon and Pontolis kohnoi are both from the same geological rock layer as the 2018 study by Parham and his students of another new genus and species of a tuskless walrus, Titanotaria orangensis, named after CSUF Titans. These fossils were found in the Oso Member of the Capistrano Formation, a geological formation near Lake Forest and Mission Viejo.

The third new walrus species, Pontolis barroni, was found in Aliso Viejo, near the 73 Toll Road. It is named after John Barron, a retired researcher from the U.S. Geological Survey and world expert on the rock layer where the specimens were found, Parham said.

Evolutionary History of the Walrus

Analysis of these specimens show that fossil walrus teeth are more variable and complex than previously considered. Most of the new specimens predate the evolution of tusks, Parham said.

“Osodobenus eodon is the most primitive walrus with tusk-like teeth,” Parham said. “This new species demonstrates the important role of feeding ecology on the origin and early evolution of tusks.”

Biewer explained that his work focused on getting a better understanding of the evolutionary history of the walrus in regards to its teeth.

“The importance of dental evolution is that it shows the variability within and across walrus species. Scientists assumed you could identify certain species just based on the teeth, but we show how even individuals of the same species could have variability in their dental setup,” said Biewer, who earned a master’s degree in geology in 2019.

“Additionally, everyone assumes that the tusks are the most important teeth in a walrus, but this research further emphasizes how tusks were a later addition to the history of walruses. The majority of walrus species were fish eaters and adapted to catching fish, rather than using suction feeding on mollusks like modern walruses.”

Biewer, now a paleontologist in the Modesto area, also examined whether climate changes in the Pacific Ocean had an impact on ancient walruses. His work suggests that a rise in water temperature helped to boost nutrients and planktonic life — and played a role in the proliferation of walruses about 10 million years ago, and may have contributed to their diversity.