In search of treatment for Chagas disease, which kills thousands each year, Cal State Fullerton infectious disease researchers have discovered an important new mechanism that can be exploited as a target for potential drug development.

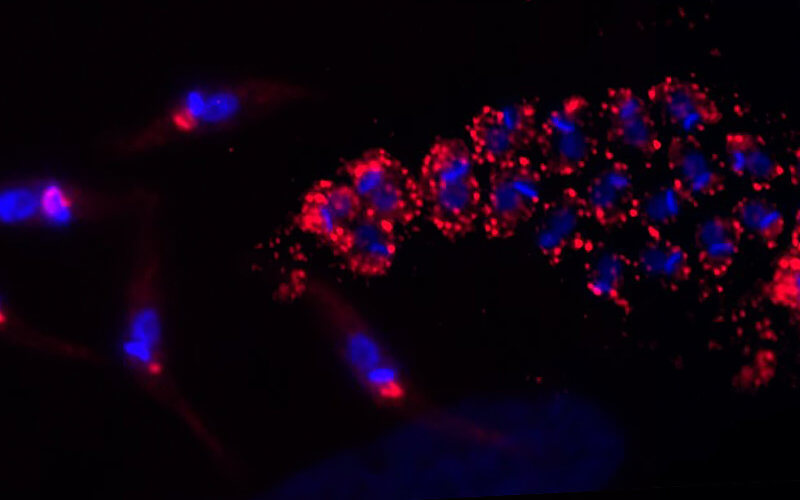

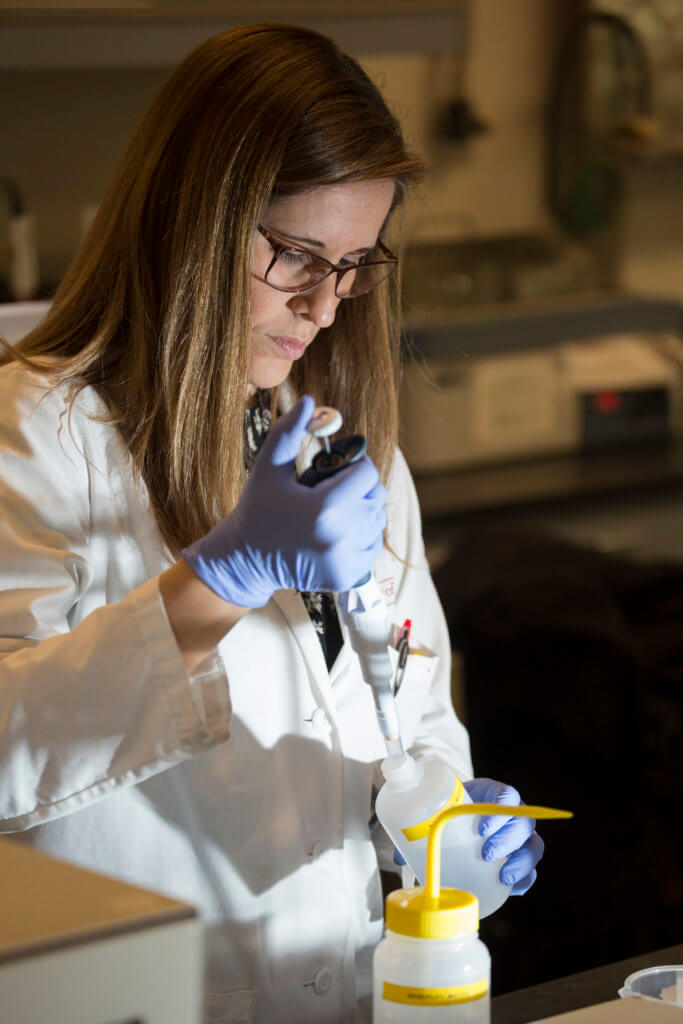

Veronica Jimenez, associate professor of biological science, and her former students describe how Trypanosoma cruzi, the parasite that causes Chagas disease, can sense its internal and external environment in a new study published in eLife.

“These sensing mechanisms were not previously known. Our work is pioneering the field of mechanosensation in parasites,” said Jimenez, co-author of the research.

Jimenez’s former student Noopur Dave is lead author of the publication, which was the basis of her master’s thesis.

Dave ’13, ’17 (B.S. biological science-cell and developmental biology, M.S. biology) is now a doctoral student at Indiana University, School of Medicine in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology. With the support of Jimenez, she also is an American Heart Association predoctoral scholar for her current research on the human parasite Toxoplasma gondii.

“This is the first scientific work that highlights the functional role of a mechanosensitive channel in the human parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Mechanosensitive channels are a unique group of ion channels that are used by humans in functions such as sense of touch and hearing,” explained Dave.

However, the function of these mechanosensitive channels in the parasite was poorly understood. The researchers found that the particular mechanosensitive channel they studied, called “TcMscS,” is important for the survival of the parasite.

“The channel TcMscS is unique to the parasites, and not present in humans, which represents a big advantage as a possible therapeutic target because it can be selectively blocked,” Dave added.

“Specifically, we found that TcMscS plays a role in the ability of the parasite to maintain cell volume and shape under different osmotic conditions. We also found that TcMscS is important in the ability of the parasite to infect human cells — and that the channel itself can be a potential drug target.”

Chagas disease, spread by insects called triatomine bugs or “kissing bugs,” is on the rise in the U.S. — the first case in Nebraska was reported this summer. A recent study also suggests doctors are underdiagnosing the potentially life-threatening illness, which can cause heart and digestion problems.

These blood-sucking triatomine bugs get infected with the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite by biting an infected animal or person. The bugs often bite people’s faces, earning the nickname “kissing bug.” Once infected, the bugs pass the parasites in their feces.

In the U.S., more than 300,000 people are infected with Chagas, while in Latin America, an estimated 6 to 7 million people have the disease.

The research team’s discovery can lead to new and better drug therapies against Chagas disease and other parasitic diseases, Jimenez added.

“We have no vaccines or good medications to treat it, so the development of new drugs is a priority,” Jimenez said.

Jimenez’s other former students who are co-authors of the paper and worked on the research project as undergraduates or graduate students also are pursuing graduate school.

These co-authors are alumna Megna Tiwari ’19 (M.S. biology), now pursuing a doctorate at the University of Georgia; Joshua Fonbuena ’19 (B.S. biological science-molecular biology and biotechnology), a former Maximizing Access to Research Careers (MARC) scholar and a doctoral student at the University of Utah; and, Daniel Arroyo ’19 (B.S. biological science-cell and developmental biology) who plans to attend medical school. The CSUF researchers collaborated with Sergei Sukharev, professor of biology, at the University of Maryland.

For Dave, her undergraduate and graduate research experiences as a Titan solidified her passion to become an infectious disease scientist and inspired her to pursue a doctorate.

“Being mentored by Dr. Jimenez, I learned basic molecular and cellular biology methods, how to formulate a hypothesis-driven project, and along the way managed different aspects of the project, while mentoring other students and personnel of the lab,” she said. “It was truly a role that taught me the challenges and the rewards of managing my own project through the guidance from a great scientist and mentor like Dr. Jimenez.”