In a basement laboratory, Cal State Fullerton biology graduate student Chelsea Bowers dissects Pacific sardines and blends them into a creamy “shake.”

It won’t go well with a burger and fries, but her hope is that the concoction of sardine stomach and muscle tissues will help find solutions to microplastic contamination of ocean life.

Bowers’ ongoing research studies how such marine pollution may be affecting Pacific sardines, an essential part of the oceanic food chain and a commercial food fish that ultimately leads to our dinner tables.

Her hope is that this research, which aims to quantify ingested microplastics — the amount, size and type — found in the sardines’ stomachs and muscle tissues, will help other scientists studying a growing and international microplastics problem.

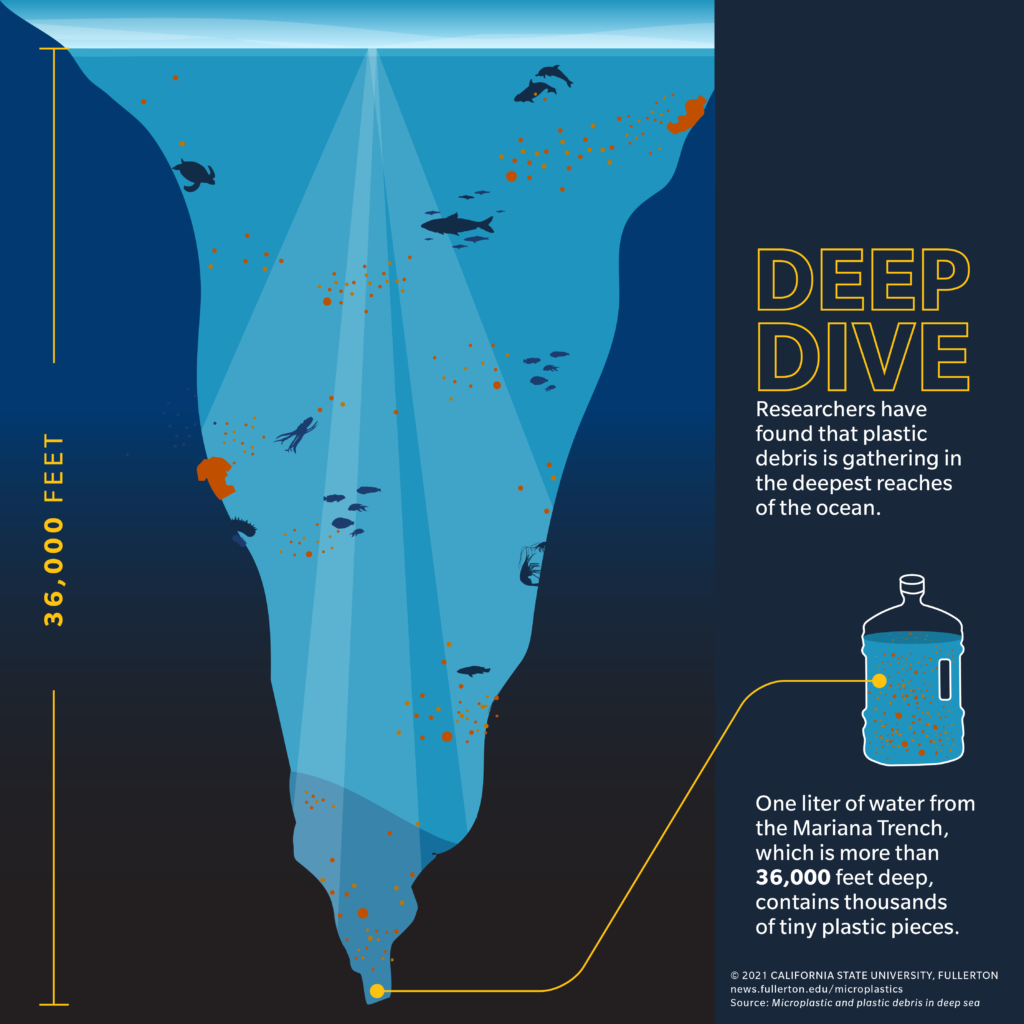

A study by researchers from the Netherlands and New Zealand predicts that without proper handling or removal of already-accumulated plastic pollution, the world’s microplastics problem could double in size by the year 2050. Irish researchers found that 73% of deepwater fish in the north Atlantic Ocean had eaten particles of microplastics, while a Harvard study estimated 14 million tons of microplastics exist on the whole ocean floor.

Fishing for Answers

Bowers’ preliminary research findings show microplastic contaminants in wild-caught sardines.

“I’m finding microplastics in the stomachs and muscle tissues of the sardines, which is what you hope you don’t find,” she relayed. “These findings ultimately could help build the foundation for future research concentrating on physiological pathways of assimilated microplastics in sardines and potentially other fishes.”

Bowers, who expects to finalize her study next year, started collecting sardine samples in September 2019. While the pandemic stalled her work, she is now back in the lab — following university COVID-19 safety protocols — to dissect the sardines and analyze tissue samples.

The Pacific sardine is found along a stretch of curved coastline known as the Southern California Bight winding from Point Conception, near Santa Barbara, south to the U.S.-Mexico border and seaward toward the Channel Islands.

Bowers is specifically looking at Pacific sardines caught off the coast of Long Beach.

This blue-greenish sardine, which can grow more than a foot long, is commonly used for bait, as well as for animal and human consumption. The small fish is prey for other marine life, including seabirds, and is found in local coastal waters, especially between the spawning months of August through October.

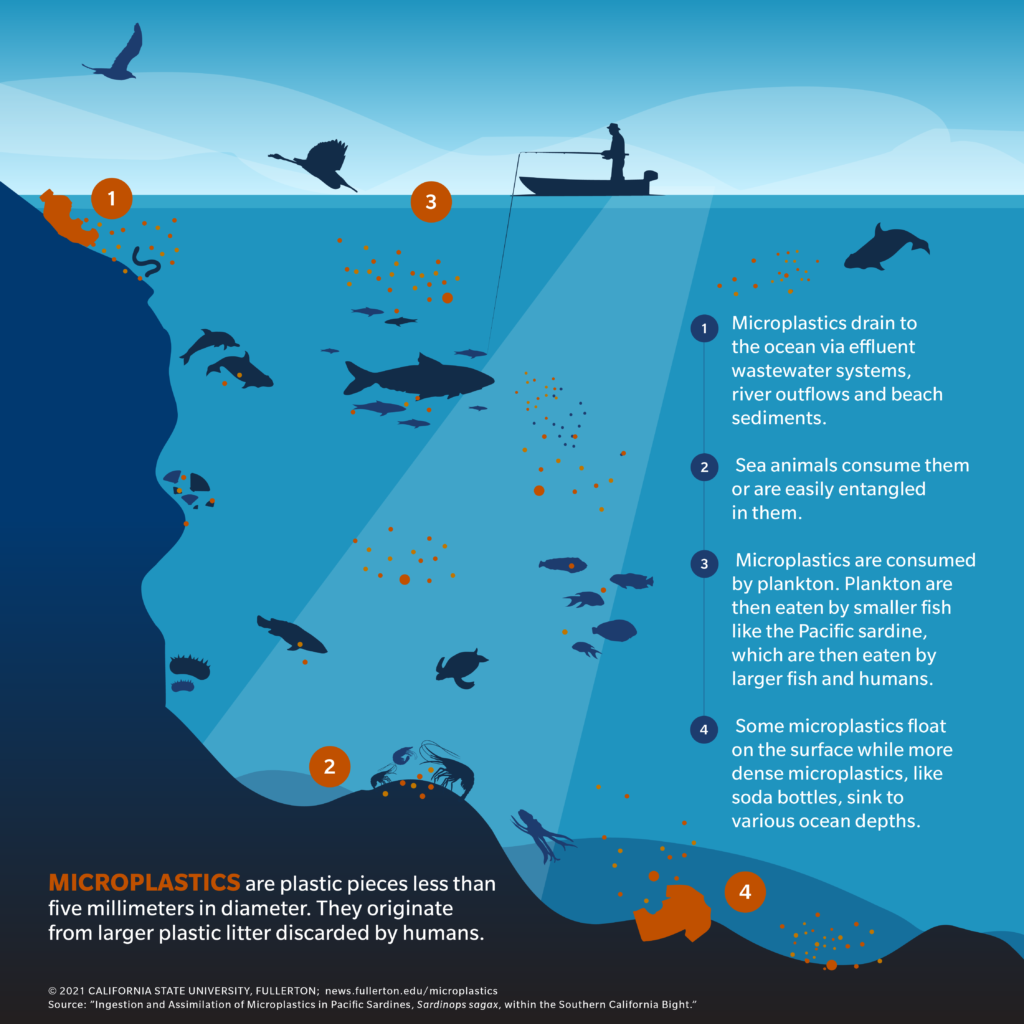

“Pacific sardines are filter feeders that feed on a variety of plankton in the same size range as marine microplastics and are vulnerable to ingesting microplastics,” Bowers said. “More and more plastics are being degraded into our coastal waters as a result of contamination from river run-off and wastewater.”

Microplastics in the Environment

Misty Paig-Tran, associate professor of biological science and Bowers’ research adviser, noted that microplastics are either manufactured directly, such as plastic beads in exfoliating scrubs and toothpaste, or are broken down from larger plastics like Styrofoam food containers, straws, bottles, caps and other plastic litter discarded by humans.

“These may be virtually undetectable to the human eye in the water, but they can be quite harmful to marine life,” she said.

While microplastics are found worldwide, even in the most remote waters on Earth, their impacts are just now coming to light through research efforts, Paig-Tran added.

A study by scientists in Malaysia found microplastics in the muscles of canned sardines, but not in the canning solution, the researchers explained.

“It’s unclear if the microplastics were from the manufacturing process or if the animals were ingesting the plastics while living wild in the ocean,” Paig-Tran said.

Diving Into a Marine Science Career

Bowers earned a bachelor’s degree in biological science-marine biology in 2018 from CSUF and enrolled in the graduate program in fall 2019. She has received funding for her work through a variety of sources.

She was awarded a 2020-21 COAST (CSU Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology) graduate student research award and a Coppel Graduate Student Science Award from the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. Additional funding was provided by COAST’s Rapid Response Funding Program, awarded to Paig-Tran.

Bowers’ graduate thesis is titled ”Ingestion and Assimilation of Microplastics in Pacific Sardines, Sardinops sagax, within the Southern California Bight.” As a graduate student, she also teaches an introductory lab course and is a research technician in the marine ecology lab of Danielle C. Zacherl, professor of biological science.

Her research and teaching experiences are building her future career in marine science. Bowers wants to work at a conservation agency that focuses on marine pollutants to implement management strategies for mismanaged plastic waste. She also is considering teaching at the community college level because of her CSUF work as a lab instructor.

“Dr. Paig-Tran has been an amazing mentor. She saw something in me that I couldn’t fathom until I returned to CSUF to further my education,” Bowers shared.

“She is consistently helping me grow into an even more dedicated and hard-working female scientist and has helped me attain goals that I didn’t think were possible. I went from working as a bartender to an award-winning scientist studying marine pollutants.”