Sepi Esfahlani knows people who are “sitting out,” refusing to vote in the presidential election.

“They don’t agree with Hillary’s type of feminism,” she told political science panelists at a recent presentation, “Women and the 2016 Election.” And when she asks about local and state elections, their answer is often apathetic shoulder shrugging.

Polls show many voters feel they must choose the presidential candidate they dislike the least. With Hillary Clinton as the only woman to win the presidential nomination of a major party, feminism is in focus too, panelists said.

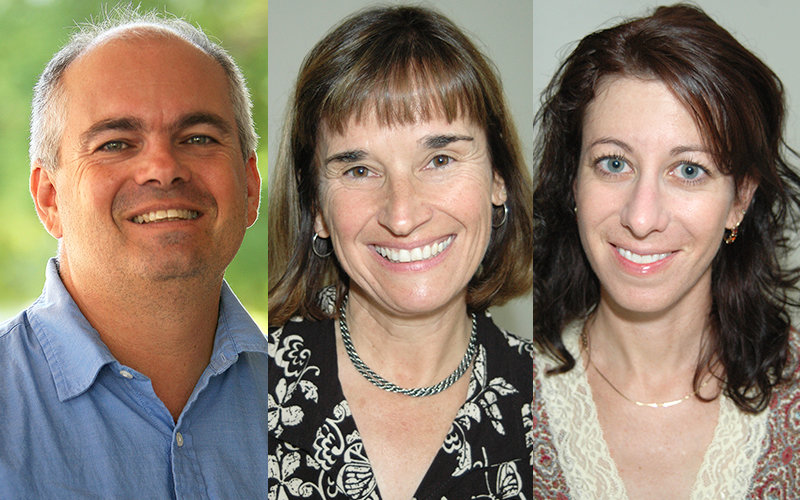

Clinton has to make sure she doesn’t violate what it means to be a woman while tackling issues-assigned gender norms, and still demonstrate that she’s a tough candidate, said Pamela Fiber-Ostrow, associate professor of political science.

If elections weren’t so candidate-centered, the U.S. would have a model that was more female-inclusive, she said. Issues like parental leave, childcare and education are often labeled “women’s issues,” she said. “But it’s a human trait to want to see improvement in our communities.”

Many countries benefit from female leadership and quotas requiring a minimum percentage of female representation, Fiber-Ostrow said. Women lead or have led for generations in the United Kingdom, Norway, France, Germany and elsewhere.

But in the U.S., female political candidates often face a lack of party and voter support, prejudicial media coverage, a biased electoral system and their own lack of confidence. “As a result we’re trying to figure out what we need to do to change this,” Valerie O’Regan, professor of political science, added.

Change, and realizing the benefits of women in politics, requires looking back first, says Stephen Stambough, professor of political science.

Women have lacked a strong and sizeable pipeline of potential candidates. Historically, political candidates were military and business leaders (mostly men) until changes in the last decade, he said. Studies show that at a local level, people tend to start political careers between ages 25 and 35, and women often wait to be asked to seek office. But the two-party system wasn’t asking women, he said. In previous eras, female candidates were surrogates for deceased political spouses or the “sacrificial lamb” — a woman nominated for a seat she could not win.

Change is slow “and it really is starting with this generation and age,” he told the group of mostly students. “If you want to see change, then do that … run, so we can start to see change,” he encouraged.

The Division of Politics, Administration and Justice; Department of Women and Gender Studies; and the WoMen’s and Adult Reentry Center hosted the Oct. 11 panel talk.

Saba Ansari said she enjoyed the open discussion outside the classroom.

“It’s really easy to state the problems, but harder to find the solutions we need,” said the sophomore studying chemistry, a field she says could benefit from more women also. “I want to make things more equal, so future generations don’t experience the same sexism.”

Other Campaign 2016 stories:

Health Care Policy Expert Examines Partisan Divide

CSUF Experts and Students Critique the Vice Presidential Candidates

CSUF Experts React to First Presidential Debate

Secretary of State Alex Padilla Joins CSUF’s Efforts to Register Young Voters

The Millennial Vote

Political Experts Discuss the Possibility of a Brokered GOP Convention

CSUF Experts Use New Campus Website to Judge Presidential Candidates During Live Debates

Campus Political Science Experts Say Fear Drives Voters