An unexpected turn in Dydia DeLyser’s research career led her to play a part in the naming of two craters on the moon to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 8 space mission.

The Cal State Fullerton associate professor of geography and the environment had been working for more than 20 years as archivist for William A. “Bill” Anders — a retired U.S. Air Force major general and NASA astronaut who traveled to the moon Dec. 21-27, 1968 — when they learned that the International Astronomical Union was interested in paying tribute to the voyage on its golden anniversary.

DeLyser, Anders and Smithsonian planetary scientist Bob Craddock put together a presentation for the IAU, the authority responsible for the naming of planetary features in the solar system, asserting that the craters Anders had named in preparation for the mission — later changed amid Cold War tensions and the space race — should be restored to Anders’ original names.

“One of the objectives of Apollo 8, since they would be the first human beings to ever see the far side of the moon, was to understand and identify features on the moon,” said DeLyser.

In the tradition of explorers, DeLyser explained, Anders named three craters after fellow astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and himself. These names were marked on maps until 1971, when the IAU, in a Cold War compromise with the Russians, moved Anders’ names to lunar craters the three astronauts had never themselves seen.

This led Anders to pursue a nearly 50-year effort to have the names returned. Following his latest presentation, the Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature of the IAU approved the naming of two craters on the moon and announced them on Oct. 5: “Anders’ Earthrise” and “8 Homeward.”

“In the end, the working group said they could not restore Anders’ original names,” said DeLyser. “Instead, they offered to name two new craters in honor of Apollo 8.

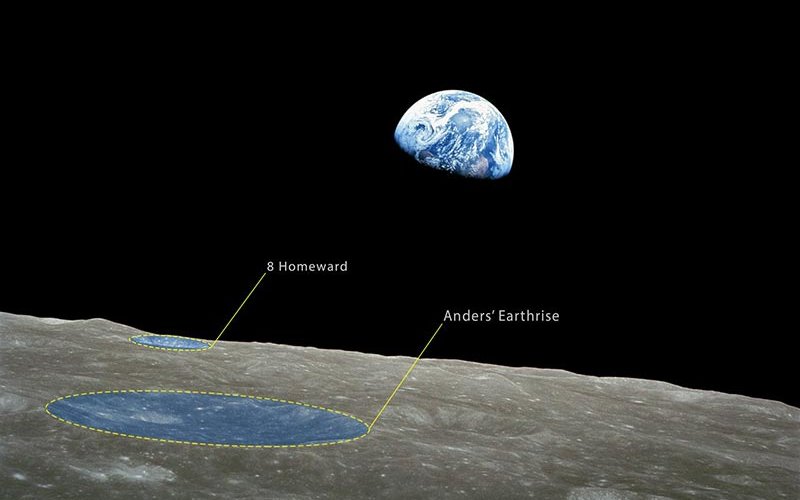

“‘8 Homeward’ marks the moment Commander Borman fired the rocket engine to send the spacecraft back home — the first time humans would return home from another planetary body — and ‘Anders’ Earthrise’ honors the influential photograph taken by the major general,” she continued.

Both craters are visible in Anders’ “Earthrise” photograph, which captures the blue Earth over the barren surface of the moon. The image is said to be one of the most iconic of the 20th century and is credited with inspiring the environmental movement.

DeLyser, who teaches such courses as “Global Geography,” “Cultural Geography” and “Geographic Research Design,” shared her research experience with students, faculty members and the community during CSUF’s Nov. 2 “All Points of the Compass” geography symposium.

Asked by the audience how Anders felt about the decision, DeLyser said she believes he is pleased with the naming, which ultimately honors the legacy of the astronauts who became the first human beings to leave low Earth orbit, reach and orbit Earth’s moon, and return safely to Earth.

“We normally think of politics as only pertaining to the Earth, but we can see from this example that they extend as well to the moon,” said DeLyser.

“I began my own undergraduate career in geography eager to learn about our world, to help people understand it, and to help protect and preserve it,” she shared. “What I never expected was that geography would take me all the way to the moon, and that I’d have a chance to have even some small influence on the history of another planetary body.”