Barbra Erickson, professor of anthropology, has had a lifelong interest in diseases and parasites. As an anthropologist, she studies the growth and spread of disease in relation to the total environment — considering cultural, social and physical factors.

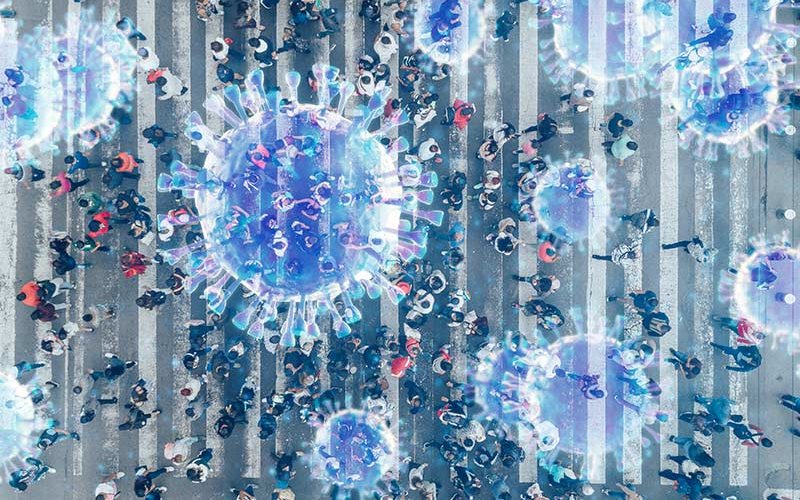

The new coronavirus (COVID-19) is an example of a “crowd disease” — the type that has only impacted humans since they began to live in dense populations. Modern life, she says, allows such a virus to be transmitted globally in a short period of time.

“Our dense cities, crowded subways, airplanes and buses, as well as popular forms of entertainment like large events in stadiums and trips on cruise ships, make us uniquely vulnerable,” says Erickson, who teaches such courses as “Medical Anthropology,” “History of Anthropology” and “Psychological Anthropology.”

“It is our cultural behavior — the way we live, the way we travel, our huge population — that exposes us to particular kinds of health risks.”

How does population growth impact the likelihood of such viruses as COVID-19?

Viruses, which attack our bodies at the cellular level, consist only of genetic material and a protein coat; they cannot survive without a host. With a large host population in which to circulate, such as we have in today’s world, viruses have a nearly unlimited supply of new hosts. In contrast, for the vast majority of human history people lived in small groups as hunters and gatherers. Small groups — say, 50 or 100 people — could not support infectious viral diseases such as smallpox, influenza, measles, or something like today’s coronavirus. If such small groups did contract a virus, they might all be killed by it; if any survived, they would then be immune.

Furthermore, many of the pathogens that cause infectious diseases in humans can be traced directly to our destruction of the environment. As the human population grows, we continually encroach upon wildlife habitat for farms, towns, cities, factories and airports — putting us at risk for increasing numbers of pathogens. The result is that dense populations of humans then provide ideal conditions for infectious diseases to spread among vast numbers of victims.

How does climate change impact the growth and spread of disease?

The climate in which people live makes possible — or not — certain kinds of pathogens. For example, many more insects, parasites and pathogens naturally thrive in warm tropical climates than in cold arctic climates. As the global climate warms, we can expect the range of insects such as mosquitoes, ticks and flies to expand to places that were once too cold for them. Many diseases are transmitted by insects, including Lyme disease, malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, sleeping sickness, West Nile virus and more.

Climate change today is causing more extreme weather events. In the U.S., many areas have been affected by severe flooding from excessive rain and from hurricanes. Although we seem to have escaped it so far in the contemporary U.S., water-borne pathogens such as cholera can quickly infect and kill many people when drinking water is compromised.

We humans have already upset the ecological balance by changing so much of the environment for our own purposes, not to mention polluting it. We can assume that climate change will also shift the ecological balance and potentially expose us to still more pathogens.

What can we do to prepare for the rise of new pathogens?

We can be sure that the current pandemic won’t be the last one. Ideally, people must accept the scientific facts of global climate change, and that this will contribute to our collective exposure to new pathogens. Politics and cultural beliefs incline governments to deal with health threats in different ways. But it seems to me that our only hope for dealing with the inevitable pandemics of the future will be to work together to preserve the environment as best we can, and to think of ourselves collectively as one human species that must cooperate and share information, especially scientific knowledge about vaccines and treatment. As many have said, neither climate change nor pathogens recognize political borders or cultural boundaries.