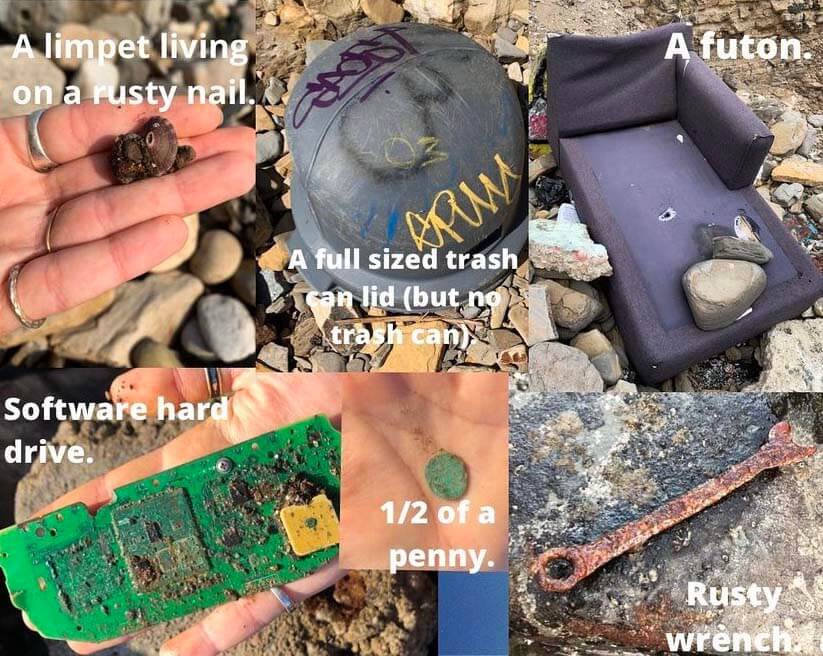

A futon. A car wheel with its axel. A computer hard drive. An electric scooter. And small items like a rusty nail, where a limpet — an aquatic snail — made its home.

These are just some of 6,740 pieces of human-discarded trash Trina Miller discovered in the rocky intertidal zone — the shoreline area between high tide and low tide — at her three research sites in San Pedro.

Miller, a Cal State Fullerton biological science major, is focusing her research project on identifying and categorizing ocean trash to determine the threats of human-caused debris to marine life in the rocky intertidal zone. This important and biodiverse marine ecosystem along the rocky shores is where plants, seaweed and animals such as mussels, sea anemones and sea stars, live.

Glass pieces were the most common type of human-created debris Miller found, along with a variety of metal items, including aluminum cans and spark plugs, and plastics — everything from bottles to food wrappers and foam containers.

“Trina has developed and pioneered methodology for categorizing and quantifying marine debris in the rocky intertidal zone,” said Jennifer Burnaford, professor of biological science, and Miller’s research adviser. “She has presented her findings at multiple professional conferences and is preparing herself for a career in marine conservation.”

Miller’s research findings show how much and what kind of trash is present at Point Fermin Park, Sunken City and White Point Beach, with each research site having a distinct trash profile. The amount of trash was not the same at all sites. Sunken City had the highest amount of trash and White Point had the lowest amount of trash.

Additionally, the top debris categories are different from trash usually found on sandy beaches, which highlights the importance of continuing research in the rocky intertidal zone, Miller said.

The repeated encounters of individual items also reveal how effective and important beach cleanups can be in preserving rocky intertidal habitats. Her data also suggest the litter at each of the sites seems to be originating from terrestrial activities, rather than washing up from the ocean.

“I did not remove any trash in order to monitor the change in concentration of trash throughout time,” said Miller, who is studying marine biology. “This allowed me to create a baseline of information of how much and what type of trash is present at any given point in time at my sites. My research is helping to build an understanding of this massive issue.”

The majority of trash research is focused on sandy beaches, open ocean and inner city areas, but little is known about the type and amount of trash in the rocky intertidal zone. While one of the biggest issues worldwide is the plastic epidemic, Miller became interested in investigating macroplastics — anything bigger than 5 mm, or the size of a pencil eraser.

Miller is a scholar in the university’s Southern California Ecosystems Research Program (SCERP), which focuses on ecological issues. She grew up next to the ocean in Redondo Beach and has always been passionate about sustainability and conservation. She discovered that little is known about the amount and type of trash strewn within the rocky intertidal environment.

“I specifically wanted to study macroplastics because I did not see the use in waiting until larger pieces of trash degrade into small pieces. The rocky intertidal zone is an important habitat ecologically, and in order to help solve a problem, you must know the extent of it,” she said.

Her research project is supported by donations to SCERP and grants from the California State University Council on Ocean Affairs, Science and Technology. She embarked on her project during the height of the pandemic in August 2020 and was able to conduct fieldwork beginning in spring 2021 while following safety protocols. She monitored the three coastal sites once a month for almost a year.

Through her study, Miller hopes to raise awareness about the alarming amount of litter that makes its way into the ocean and offer vital information that can help with management and conservation decisions.

Miller is currently analyzing the data she collected in the field, writing her senior thesis paper and is planning to submit her research for publication.

“I would not be the scientist I am today without SCERP. This incredible program has provided me with a sense of community, professional development, mentorship and a plethora of research opportunities,” said Miller, set to finish her studies this fall semester and graduate in January.

Other CSUF research projects Miller has been involved with as part of her coursework include data analysis on the effects of an abnormal marine heatwave off the West coast on fish populations, calculating the density and abundance of native and nonnative oysters in San Diego and contributing to documentation of sea turtle conservation efforts in Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Her undergraduate research experiences have given Miller confidence in her scientific abilities and prepared her to work in the field of marine ecology and conservation.

“I hope to continue to help make positive changes in the environment and educate people on why sustainability and conservation are so important — and how they can pay tribute to the scientific community in their day-to-day lives.”

Follow Miller and her research on Instagram: @trina_tracks_trash and @burnaford_lab