Cal State Fullerton geologist Kathryn Metcalf is searching for clues into the collision of India and Asia over 60 million years ago that created the Himalayas, the world’s tallest mountain range straddling Tibet and Nepal.

Before the two continents collided, not long after the dinosaurs went extinct, India was a large island in the Indian Ocean and far south of Asia.

The Himalayas — Mount Everest is the highest peak — have been studied extensively. Yet, researchers debate the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates, which closed the ocean between India and Asia.

“The India-Asia collision is the largest ongoing continent-to-continent collision, raised the highest mountains in the world and has significantly altered global climate,” said Metcalf, assistant professor of geological sciences, who studies how mountains are built.

“Despite decades of study by geologists around the world, there are several things that don’t add up about the India-Asia collision,” she said.

In her study, Metcalf is investigating whether India was twice as big as it is today, if there was another ocean in between pieces of India or Asia, and insights into how the collision occurred.

Metcalf’s study, supported by a nearly $294,000 National Science Foundation grant, focuses on untangling the deformation history — the process affecting the shape, size, or volume of an area of the Earth’s crust — during the first half of collision.

Meanwhile, the collision continues today, making the Himalayas slowly grow taller.

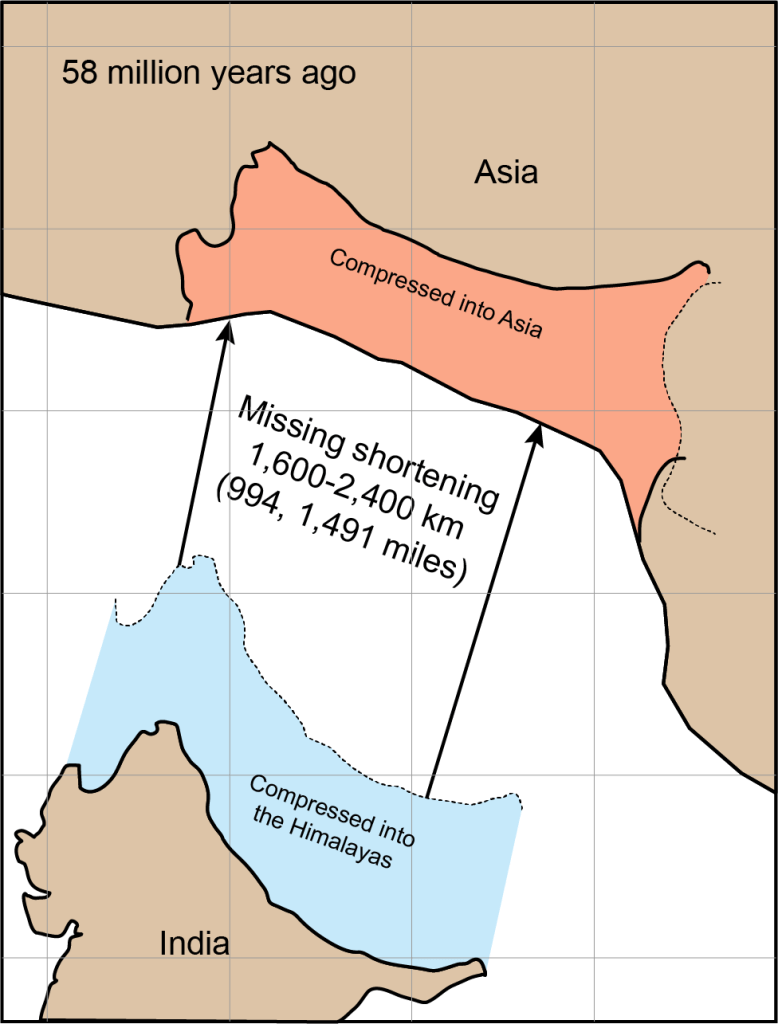

“If we rewind plate tectonics, India has moved about 1,800 miles since the continental collision began about 60 million years ago,” she said.

“Over the last 30 million years, growth of the Himalayas accounts for about 600 miles of shortening. The other 1,200 miles are missing from the rock record and is one of the greatest puzzles of the India-Asia collision.”

Some clues may be hidden in the Tethyan Himalaya, a sedimentary zone stretching from northern India into southern Tibet, a major tectonic area. Plate tectonics is the movement of Earth’s outer layer, which causes earthquakes, shifts continents and builds mountains.

Metcalf said that if she and her research team find significantly less than 1,200 miles, then that would suggest there may have been another ocean basin that had closed during the India-Asia collision.

Metcalf’s study is co-led by Delores Robinson, chair and professor of geological sciences at the University of Alabama, who is conducting lab analyses. Their research team includes graduate students from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Research in Tibet Unravels the Past

Over the past two summers, Metcalf and her students traveled to Tibet to conduct fieldwork, which included collecting rock samples to find pieces of information about the closure of the ocean between India and Asia in the geologic past.

Alumna Jennifer Diaz, a first-generation college graduate who earned a bachelor’s degree in earth science this year, was Metcalf’s student field assistant in Tibet this past summer.

The fieldwork gave Diaz the opportunity to learn new skills, such as using technology to create geologic maps and a microscope to identify minerals.

“The research was fascinating because, just by looking at the smallest details in bedrock, you can unravel the past by observing and taking measurements,” said Diaz, who aspires to become an environmental scientist.

Geology graduate student Kaelyn McFadden will examine the rock samples in Metcalf’s campus lab to understand the scale of the continental collision.

“This project is exciting because we use rocks at the surface to piece together the history and movement of the tectonic plates. When we analyze these samples, we are getting the chance to see back millions of years in time,” McFadden said.

For Metcalf, her project has allowed her to study the region further following her doctoral research in Tibet 10 years ago, which focused on the closure of the ocean between India and Asia.

Metcalf will return to Tibet next summer to continue searching for evidence about the mysteries surrounding the continental collision.

“We’re doing cutting-edge research to find solutions and expand our understanding of how the Earth works to tell us the story of plates crashing into each other — and building mountains.”