Cal State Fullerton African American history researcher Natalie Novoa wanted to learn more about the Progressive Era’s playground movement and how Black Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area fought for equal access to recreation facilities and public spaces.

Novoa, assistant professor of African American studies who grew up in the Bay Area, examined how the playground movement was ushered in at the turn-of-the-century as a social reform effort — and how the Black middle class demanded access to these public spaces.

Her study, “Defining Race, Space and Citizenship Through Play: The Playground Movement in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1900-1920,” was recently published in the Journal of Urban History.

The article is an outgrowth of her studies at UC Berkeley, where she earned a doctorate in American history in 2019. Novoa’s research interests focus on post-1865 African American history.

Novoa, a Career Enhancement Fellow in 2023-24, is also working on a manuscript, “Home Away From Home: Recreation Centers and Black Community Development in the Bay Area, 1920-1960.” The book proposal reflects her ongoing interest in studying Black experiences through urban history, recreation and leisure, and environmental history.

Why study the playground movement?

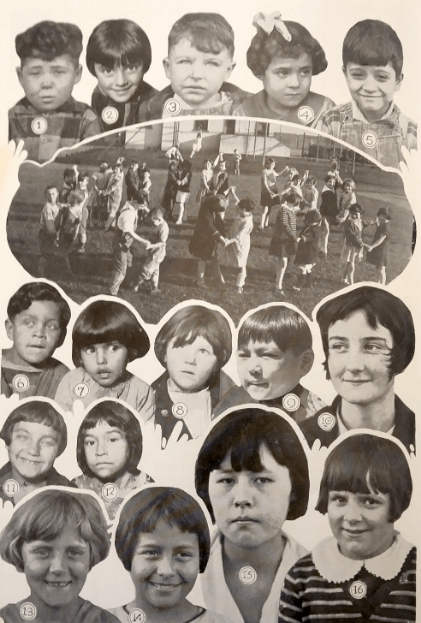

The research article examines the emergence of the playground movement and the impact it had on ideas about race and citizenship. The heart of this movement was a belief that urban communities needed access to parks, playgrounds and physical recreation. In part, it was a reaction to industrialization and fears of a perceived increase in juvenile delinquency as children and teens gained greater access to public amusements. As cities invested more in public spaces, African Americans often found themselves excluded. Focusing on the Bay Area, I’m able to trace how this process unfolded and how Black Americans advocated for inclusive policies while also building their own institutions around recreation.

What are some key findings?

One of the outcomes of this project was understanding the rhetorical shifts around race and citizenship before and after World War I. Before the war, the playground movement focused on how supervised recreation could be an agent of Americanization for immigrant children. Anxiety around increased immigration from eastern and southern Europe encouraged advocates to see the playground as a site to instill a homogenous Protestant American culture. The ‘ideal citizen’ equated to white and male. When the U.S. entered the war, recreation was seen as a way to bring different cultures and ethnicities together. For Black leaders in the Bay Area, the war provided an opportunity to demand equal access to recreational facilities and public space.

How does your manuscript examine Black community-building?

“Home Away From Home” considers the demand for and participation in recreation-alleviated racial tensions. The project explores ways in which Black-founded and Black-directed recreation centers acted as an affirmative alternative to the confrontations and humiliations that awaited them at segregated recreational venues and public amusements. My work explores why, how and with what consequences these Black recreation centers have contributed to the changing geography of the Bay Area.

In what ways does your research tie into Black History Month?

My work contributes to the long historiography of Black experiences in the West, particularly in California. I’ve always found the history of everyday people to be the most interesting lens through which to study the past. In my work, I highlight how Black residents created community, the social benefit they derived from organized recreation, and their strategies to resist segregation and exclusion. Black History Month is a time to celebrate the countless grassroots organizers who devoted their lives to fighting for their neighborhoods and cities. I hope my work expands who we remember and recognize as agents of change.