When Eric Gonzaba travels across the United States, he often wonders about the history of the places he passes through — specifically, their queer history.

The Cal State Fullerton assistant professor of American studies is the co-primary investigator and content manager of the newly launched Mapping the Gay Guides project, which plots gay spaces listed in Bob Damron’s Address Books on a digital map.

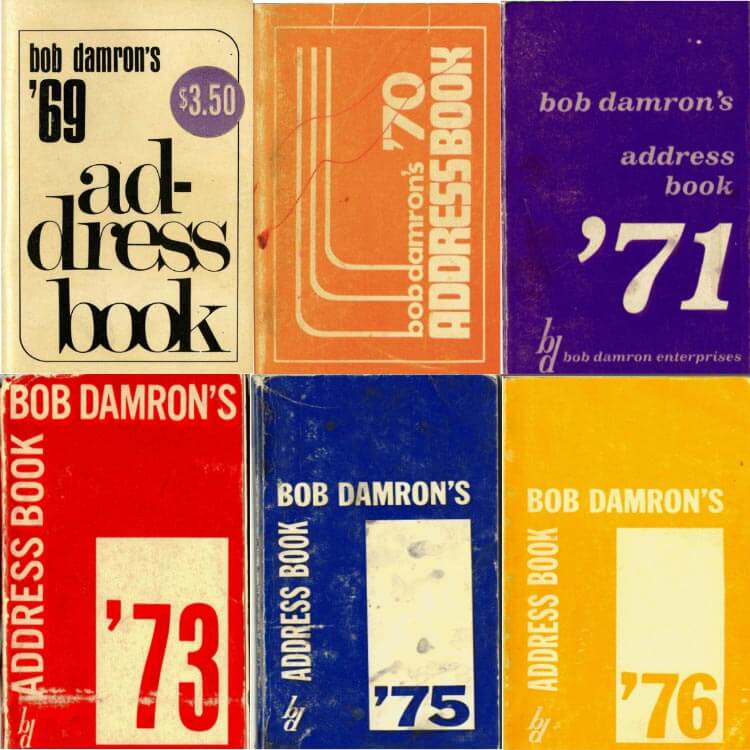

The Damron books are a series of travel guides for gay and queer travelers dating back to the 1960s. Listings include bars, cocktail lounges, bookstores, restaurants, bathhouses, cinemas and other establishments that cater to gays.

“When we think about gay history, we often think of San Francisco or New York. But there’s plenty of amazing gay history outside those cities,” said Gonzaba, noting that even a Waffle House in his home state of Indiana is listed as a former gay space.

By plotting Damron’s guides on a map, researchers can begin to see patterns over both location and time — inviting additional exploration of LGBTQ issues in America.

“It’s exciting to think that queer history is everywhere,” said Gonzaba.

The research team has mapped queer spaces in 31 states plus the District of Columbia, between the years of 1965 to 1980, with plans to map the remaining states by the fall.

America’s ‘Collapsing Gay Geography’

“Gayborhoods have long been thought of as dying,” said Gonzaba, who personally observed this while a doctoral student at George Mason University.

“When I was writing my dissertation, D.C. was losing gay bars right and left. Does that mean that there’s no more gay culture? No. It just means people’s lifestyles are changing,” he explained.

“Perhaps this kind of physical space isn’t needed anymore, whereas in the ’60s and ’70s, it was really important for gay men to have a bar in their neighborhood or to visit a city that had a space just for them.”

Mapping the Gay Guides, with its intent of offering insight into the queer world, is funded by a Research, Scholarship and Creative Activity Incentive Grant from the California State University Chancellor’s Office.

“The funding allows us to map Damron’s guides from 1965 to 1980. That’s 15 years of history, both before and after the Stonewall Riots of 1969,” said Gonzaba.

The researchers point out that the Damron address books are not a perfect source — they largely understand the gay world from the perspective of a San Franciscan, white gay man — but they are perhaps the most prolific set of listings spanning six decades.

As of 2020, Damron’s books are still in publication, though discontinuation of the guides is imminent in the internet age.

“Damron’s early guides were incomplete and sometimes inaccurate,” said Gonzaba. “But they give us a platform to begin having conversations about this collapsing gay geography.”

Introducing Students to Digital History

Working alongside Gonzaba are co-primary investigator Amanda Regan, a postdoctoral fellow at Southern Methodist University who built and manages the technical aspects of the site, and four CSUF research assistants.

Giulia Oprea, an American studies graduate student, inputs listings from Damron’s address books into Airtable, a program similar to Excel.

“Building a digital history project is very intricate and requires a lot of careful precision, especially in ensuring that the data is as clean as possible before using it,” said Oprea.

In addition to learning new skills and knowledge about digital history, the project allows Oprea to “feel closer to queer history” by studying the many layers of it.

“As a queer person, I was eager to be a part of academic work that honors our queer ancestors and understands the way that they moved throughout the world,” she said. “The project uncovers some of the silences of queer history by showing all the places that we frequented, places that are perhaps no longer in existence or that have been forgotten as queer spaces as time went on.”

Oprea, who also received her bachelor’s degree from CSUF in 2018, plans to pursue a doctorate with the goal of teaching and publishing her own research.

“I think that one of the most important things we can do when it comes to queer history is ensure that the work of people before us doesn’t die with them.”

Open Datasets for Researchers

“The point of digital history is not to confirm what we already know. It’s to try to find things that we didn’t,” Gonzaba emphasized.

For example, the research team was surprised to find more than 7,000 listings for gay spaces in the South, between 1965 to 1980.

“We’re shocked by the sheer number of listings in the South, which people think of as inherently homophobic. Damron’s guides suggest there was plenty of gay culture in the South, even before Stonewall.”

Other observations are more insidious, he said. Spaces labeled “blacks frequent” (B) in the guidebooks, are likely to also be labeled “raunchy types” (RT), a term Damron links to places full of vice, crime and deviance.

“We don’t know if that’s intentional or not, but I think there’s plenty to explore in terms of Damron’s projections of how African Americans are portrayed in the gay community.”

The team is most looking forward to seeing the data from the 1980s, said Gonzaba. “We want to see what happens to the gay world during the AIDS crisis.”

One misconception of digital history, he said, is that projects will live forever on the internet. “People think when you digitize something, you don’t need the physical copy anymore. But data is destroyed all the time on the internet.”

To that end, the research team’s long-term goals are to find a reputable institution to house the data on its servers in perpetuity — without censoring or withholding any information — and to secure funding to plot the rest of the guides, from 1980 to the present.

“Our methods and our ethics tell us that the data is not ours. It’s for everyone, and especially researchers, to use,” said Gonzaba. “We want people to have access to this data, so they can begin to ask their own questions.”