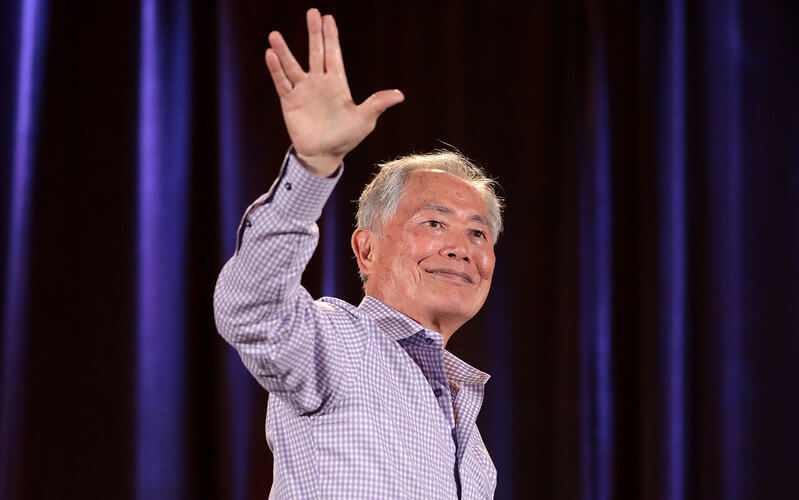

About 20 years ago, Craig Ihara, professor emeritus of philosophy and Rohwer, Arkansas internee, sat down with George Takei to discuss the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, Takei’s activism on behalf of Asian Americans, and, of course, his acting career.

Twenty years later, after viewing the interview, it is clear to Ihara that America still has much progress to make.

“The rise of anti-Asian violence makes this year, particularly, a relevant one to hear from someone who was unjustly affected by anti-Japanese prejudice back then,” said Ihara. “The lesson we never seem to learn is not to blame individuals for things others who look like them might have done.”

This year, Cal State Fullerton students, faculty, staff and friends of the campus are reading Takei’s graphic autobiography, “They Called Us Enemy,” as part of the university’s “One Book, One CSUF” program.

Discrimination Against Japanese Americans

In the recorded interview, Takei said his mother, although born in the U.S., was sent to Japan to attend school for several years and returned when she was 21. His father was born in Japan but came to the United States at age 10.

“My American-born mother came back at age 21 and was very Japanese, and my Japanese-born father was very American,” he laughed. His parents met in Los Angeles and had three children.

“There was discrimination before the war,” Takei said. “My college-educated father couldn’t get a job commensurate with his education and this was common among Japanese. My family operated a cleaning business.”

Takei recalled when “scary soldiers with guns” came to his home one evening when he was four years old. His father told him they were going on a long vacation in the country. The “vacation” began with a stay in the horse stables at Santa Anita Racetrack.

“I didn’t really mind,” he said. “As a kid, I was excited to stay where the horses were. I thought this is how people took vacations.”

Incarcerated in Rohwer Camp

Eventually the Takei family would be brought to the Rohwer Camp in Arkansas. He remembered the long train ride where the windows would have to be closed when they approached towns and cities so the citizens weren’t aware that busloads of Japanese Americans were being sent to the camps.

Years later, when Takei would ask people about the internment camps, he was astonished by people who said they had no idea this was happening.

“I have faith in our Constitution and we need to be confident enough to see where our ideals have failed,” he said. “The Reparations Act was a step toward acknowledging the wrong that was done to Japanese Americans.”

The initial draft of the act called for spending $50 million on education to inform Americans of this chapter in the country’s history and each person who was interned was to receive $20,000. However, there were more survivors than anticipated and the education funds were cut to $5 million.

Ihara mentioned he was most impressed with the positive and patriotic attitudes of both Takei and his family.

“One thing I’d like people to learn from the interview is that Japanese Americans during WWII were innocent of any of the charges raised against them and that though they weren’t white, they – like so many non-white immigrants – were just as American as anyone else,” Ihara said.

During the interview, Takei said one of his most ironic memories is of saying the Pledge of Allegiance in the camp’s classroom while looking at the barbed wire outside the window.

“What happened didn’t just hurt Japanese Americans but did damage to the American Constitution,” Takei said.

Takei says he became more involved in advocacy efforts after seeing Black citizens during the Civil Rights Movement.

“I started thinking, that applies to us as well,” Takei said.

Flawed Loyalty Oaths and Starting Over

When America started feeling a shortage of “manpower,” a loyalty questionnaire was administered to those in the camps. Yet, the way questions were presented could be damaging, Takei said.

For instance, question 28 asked, “Will you swear your loyalty to the USA and forswear loyalty to the Emperor of Japan?” As Takei noted, many wouldn’t answer the second question because it presumed that Japanese Americans were loyal to Japan. Takei’s parents refused to answer “yes” for that very reason.

When Takei’s family was finally released from the camps, they ended up on Skid Row for several weeks. Many people didn’t want to rent to Japanese families. Eventually, Takei said his father was able to open a grocery store but didn’t like to talk about the internment experience.

“When I asked him why, he said it was because despite the horrific experience, he believed in the ideals of American democracy,” Takei said. “America is still the best but the fallibility lies with the people. Democracy is only as good as the people.

“They were humiliated,” he continued. “When you are humiliated, you don’t like to talk about it. The fact that they were not viewed as American citizens hurt.”

Set a Course for ‘Star Trek‘

Takei also discussed his role as Lt. Sulu in “Star Trek.” He took great pride that he, as a Japanese actor, was playing a leading role in a popular television show and later, in subsequent movies.

“As Lt. Sulu, I wasn’t supposed to be Japanese but pan-Asian,” he said. “Gene Roddenberry’s vision, since ‘Star Trek’ was set three centuries in the future, was that people are ‘global people’ — a mixture of all races. Almost all the characters were supposed to be pan-something. Lt. Uhura was pan-African. Spock was the epitome of that as he was half human/half Vulcan. So if I was named Tanaka, that would be Japanese. Wong would be Chinese. Kim would be Korean. But Roddenberry saw the Sulu Sea in the Philippines and the water touched a number of Asian countries … so I became Lt. Sulu.

“I did have to wonder about Scotty and Chekov, though,” he laughed. “I don’t think that Scottish brogue would have lasted three centuries.

“However, he did let me keep a Japanese first name — Hikaru.”