It was a high school chemistry class that sparked Joya Cooley’s interest in becoming a chemist.

“Chemistry is the first class that clicked for me,” Cooley said. “I had a wonderful teacher who brought in guests to demonstrate how chemistry worked in the real world.”

As a Cal State Fullerton assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, Cooley uses those teaching methods with her students, including how chemistry can improve everyday products.

“Using knowledge you’ve studied from textbooks to learn about the world is empowering,” said Cooley, a 2023 Young Observer scholar.

“I try to expose my students to experiential learning opportunities, such as traveling to national labs for experiments or presenting at international conferences, to broaden their view of science and what a career in chemistry can look like, including outside the lab.”

Cooley said students earning a chemistry degree can do more than work in research labs. Chemists are needed in education, government, policy-making, and the legal field as patent lawyers and expert witnesses.

As an undergraduate, Cooley was a chemistry major and studied vocal performance. She earned a doctorate in chemistry from UC Davis before joining the university in 2020.

Cooley’s chemistry research seeks to understand how to control temperature changes in materials.

Chemistry is critical in developing new materials, such as building materials, aerospace parts and even dental fillings. For example, incorporating negative thermal expansion materials into a composite tooth filling material allows control over how much it expands.

“We study materials that exhibit negative thermal expansion — meaning they shrink when you heat them up — so you can use these materials to counteract the detrimental effects of positive thermal expansion,” she explained.

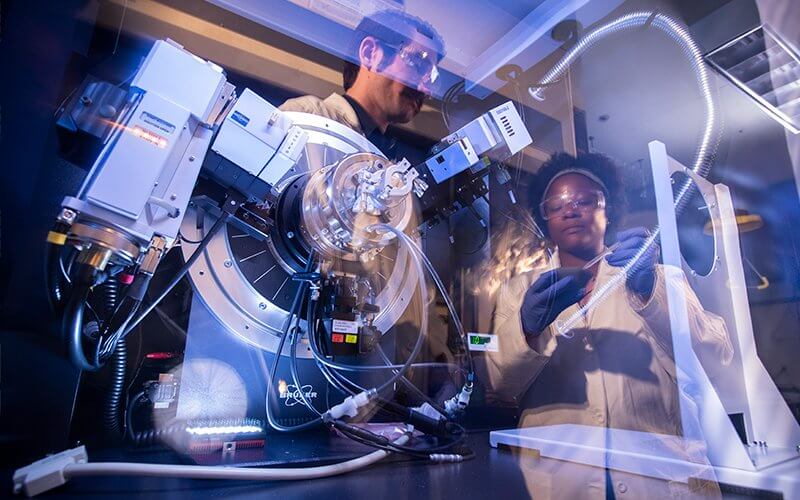

Cooley and her students synthesize different compositions of materials. They use various elements to understand how changing the elements gives some control over their negative thermal expansion.

“We want to understand how, at the atomic level, we can manipulate materials so that they will yield desirable properties to make everyday products robust and reliable,” Cooley said.

“Controlling thermal expansion is key to helping materials last longer, especially if they will be subject to large temperature differences or extreme environments.”

Cooley has garnered over $1 million in grant awards and has 18 publications, including three articles since joining CSUF. Her students co-authored two of the papers, including a new publication in the Journal of Solid State Chemistry.

In the latest publication, the researchers describe using zinc pyrovanadate, which experiences negative thermal expansion when magnesium is substituted for zinc.

“The temperature range at which the negative thermal expansion occurs did not change. However, the rate at which volume change occurred did,” said Garrett Mahler, a chemistry graduate student.

Mahler ’24 (B.S. chemistry), the first author on the publication, began his research experience in Cooley’s lab as an undergraduate.

“This was my first publication,” he said. “From the beginning, Dr. Cooley has provided me with opportunities and the tools to perform my research independently.”

Mahler, who plans to teach at a community college, has presented his research at regional and national conferences. He has also conducted research at Argonne National Laboratory and Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource.

“Once I started my undergraduate research, I discovered I had a passion for learning,” he said. “All these opportunities at CSUF have helped me to advance my research and future career.”