Marine biology researcher Katie Kern is studying chimaeras, a deep-sea fish that has no bones, but a skeleton made of cartilage and a forehead appendage with spiky teeth.

This ghostlike fish that lurks on the ocean floor might be one of the spookiest creatures of the deep, dark ocean.

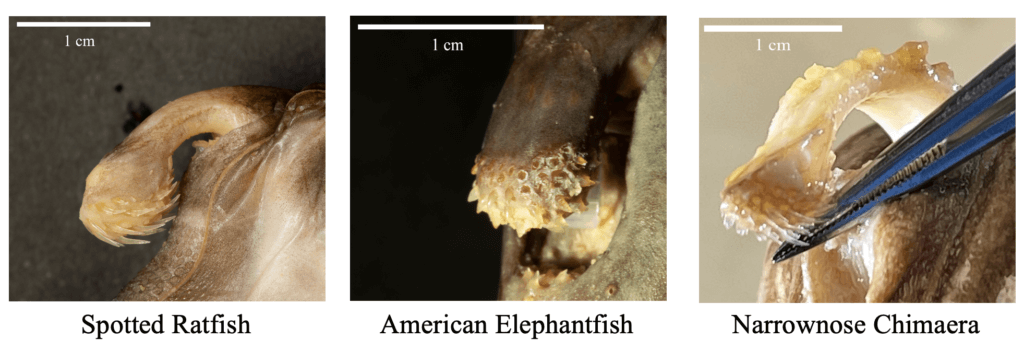

Chimaeras also are known as ghost sharks, ratfish, spookfish, rabbitfish and water bunnies. In Greek mythology, the chimaera is a mythological creature that is an amalgamation of different animals fused together, said Kern, a Cal State Fullerton biology graduate student.

The fish resembles a shark (they are distant relatives), has big round eyes like a rabbit, a long and skinny rat-like tail, ever-growing tooth plates similar to a rodent and a large venomous spine on their top fin. Some species have a large, long, elephant-like nose. Their big eyes allow them to see with no light as they creep in the dark hunting for food.

“When you see them swim, it’s easy to understand how they get their name of ghost shark as they glide along the deep ocean bottom. A few even look like the familiar pet ghost dog, Zero, from the ‘Nightmare Before Christmas’ movie,” said Kern, who first learned about the mysterious fish in an undergraduate shark biology class.

“They are sort of like the Frankenstein of animals — mashed into one charismatic fish.”

Chimaeras, anywhere from 2 feet to 6 feet long depending on the species, are found in nearly every ocean and in depths of about 6,500 feet.

When Kern first contacted her research adviser, Misty Paig-Tran, about graduate school, she immediately honed in on focusing her thesis project on chimaeras.

“It was clear that she had specific questions about the functional anatomy in a really hard-to-study fish,” said Paig-Tran, associate professor of biological science.

“She has collected more data in her first year of graduate school than any student I have ever mentored. Her enthusiasm is always apparent and infectious. The entire lab now knows and loves these critters because of Katie. I mean, who doesn’t love a spooky, weird fish?”

For her study, Kern is doing a deep dive on a special structure found only in these fish. She is investigating their functional morphology, including why the males have a forehead appendage that hooks onto females during mating.

“My research focuses on a sexually dimorphic structure, which means that males and females look different and have different body plans. The structure I’m investigating is called the tenaculum and can only be found in males,” Kern explained.

“The denticles on the tenacula are thought to help the male grab onto the slippery skin of the female during mating, which is especially helpful in deep waters where there is little light, and mating can be difficult.”

For her project, Kern is using museum specimens to look at how structures change across the three families of chimaeras. She received an American Society of Ichthyology and Herpetology award to travel to museums to collect data.

With the funding, she has traveled to the Field Museum in Chicago to photograph the museum’s collection of chimaeras and gather data. The Field Museum also loaned different specimens to Kern to bring back to the campus lab. She also is collaborating with the Los Angeles Natural History Museum and Scripps Institution of Oceanography to work with their collections, as well as with the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories to gather imaging data.

The structure on the head of male chimaeras is known as the cephalic tenaculum. The fish also has two more on its pelvis, known as the pre-pelvic tenacula.

“I’m looking at how this structure changes in the three families of chimaera who live in different habitats,” added Kern, who earned a bachelor’s degree in marine biology from Cal State Long Beach.

“These tenaculum structures have skin-teeth, also known as denticles, like a shark’s skin. However, the biggest difference is that these skin-teeth really do look like teeth.”

Chimaera denticles are sharp and pointy and these toothlike projections would feel like a small needle if touched.

“While this sounds like something from a scary movie, it’s not too strange to see in deep-sea animals,” Kern added.

To better understand how these cephalic tenacula change among the families of chimaera, Kern is taking various anatomical measurements and comparing this data to find out if there is a difference among the three families based on their ecology.

Kern, who wants to either teach marine biology at the community college level or work in collections at a museum, chose this fish for her graduate thesis research project because little is known about them.

“When I started reading about chimaera, I found them incredibly fascinating. Once I found out that they had this strange tenaculum structure, I wanted to know more about it.”

Through her study, which she plans to complete by spring 2024, she hopes to contribute to the knowledge base of these deep-sea creatures and how they may be using this structure. She also wants to show the relationship between morphology and ecology of its novel anatomical structure.

“Chimaeras originated 420 million years ago, and they have retained this structure even today,” Kern said. “They’re the only living animal in the world to have the tenacula. Through this research, we can start to understand the function of the tenacula and how chimaeras are using it to mate.”