Growing up, Susie Woo’s parents didn’t speak about the Korean War. It wasn’t until she was in college that they began to share their experiences.

Her father remembers frequenting military bases, where American GIs would give him and other hungry children chewing gum and candy bars. Her mother recounts how North Korean soldiers dragged her father from their home as she watched from a hiding place above the rafters, and how the men returned for her older sister — neither of whom she would see again.

“My parents are but two of millions of survivors for whom the war remains a deep scar,” said Woo, a Cal State Fullerton associate professor of American studies. “Hearing their stories made me want to write a social history about the war that focused on the civilians whose lives were forever changed by it.”

Woo’s new book, “Framed by War: Korean Children and Women at the Crossroads of U.S. Empire,” examines the postwar lives of Korean children and women using U.S. and Korean government documents, military correspondence, orphanage records, newspapers, magazines, photographs, and interviews.

What is the focus of your book?

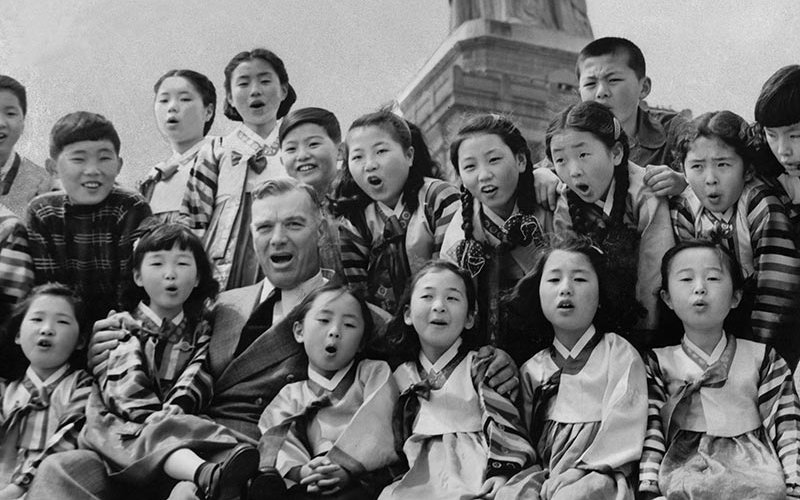

The book centers upon Korean children and women who survived the Korean War. Figured as orphans, mixed-race “GI babies,” adoptees, prostitutes and brides, they were the strained embodiments of war that brought Americans and Koreans together in intimate proximity. The book chronicles how Americans went from knowing very little about Koreans to making them family, and how Korean children and women who did not choose war found ways to navigate its aftermath in South Korea, the United States and spaces in between.

Why is it important for people to understand this subject?

The Korean War is one of America’s forgotten wars, and the experiences of Korean children and women remain even further in the shadows. Yet during and after the war, they were central to U.S. military and political strategy. Media depictions of Korean children-in-need helped garner public support, and taught Americans to understand their relationship to the far-off Asian country as parents to a foundling nation.

This internationalist narrative supported U.S. Cold War aims, but it also contributed to the actual making of international families that crossed existing boundaries of race and kinship. Today, there are more than 150,000 Korean adoptees and 100,000 Korean military brides living in the United States. It’s important to remember that this migration was sparked not by the American Dream, but by the nightmare of war.

What new or surprising information did you discover during your research?

After the war, U.S. missionaries and Americans wishing to adopt pressured Korean birth mothers of mixed-race “GI babies” to relinquish their children. In case studies, I saw photographs of Korean mothers holding their children, likely for the last time before their sons or daughters were sent to America for adoption. Their solemn expressions coupled with the age of the children, between 8 and 12 years old, signaled the extent to which mothers had tried to keep their children in Korea amidst great prejudice and shame. The photographs marked the moment when these efforts were no longer sustainable.

I knew going into this project that stories of separation would be heartbreaking, but seeing the evidence firsthand exposed the multiple layers of trauma endured by women and children, pain that they’d carry with them through lives lived apart in Korea and the United States.